After setting up a conflict, introducing the main characters, and leaving us with a mystery in Chapter 1, Lâozî gets down to business. Chapter 2 opens with a description of how things are in the established world (Heaven-below).

- Here in Lâozî’s world we have public opinion being very sure of certain things. And this kind of “firing arrows from the mouth” has defining effects on what’s not yet even born:

- First, the public is very opinionated about a particular kind of admired beauty.

- Lâozî tells us that this has an “efforting” of beauty. It lops off or defines the opposite—a disdained ugliness—already… finishing it in the womb. This is the first of 51 times we see this efforting character (wéi).

- Then public opinion is firing those certainty-arrows regarding a particular kind of traditional virtue.

- Lâozî tells us this has an efforting of virtue. It lops off or defines the opposite—a husk but not really the true inner flower of virtue—already… finishing it in the womb.

- First, the public is very opinionated about a particular kind of admired beauty.

- There are consequences of this public opinion/efforting. It means other, opposite-sounding pairs are mutually occurring/doing things together:

- Being and Not-Being are mutually birthing a bud sprouting from the ground;

- solid and changeable: mutually completing that final nail in a weapon on a pole;

- lengthy and short: mutually shaping within a hair’s breadth;

- high level buildings in the suburbs and a lower level: mutually leaning toward one another, head askew, as if an arrow’s between them;

- one tone from a moth and many sounds from hitting chimes: mutually harmonizing as a harmonica;

- forward in the front lines of battle—where a foot gets cut off as punishment—and behind—what remains afterward when stepping slowly, only the left leg leading the way, leaving only the tiniest silk thread footprints as descendants: mutually accompanying one another, walking single file near soil mountains, stopping awhile along the road.

- What a fascinating series of images, especially when read in sequence like that—it seems to paint its own story in some gauzy fashion. Then Lâozî tells us that the sun sees this list/story means some things about the grounded sage. (Throughout the 37 chapters of the Dào, whenever Lâozî says the sun’s seeing something, it sets up an objective big-picture “view from 30,000 feet.” Likewise, when Lâozî tells us about a grounded sage, it seems to be about an idealized wise person. In fact, these two phrases occur together eight of the eleven times that the sage is mentioned.) Specifically, we learn that the above list/story means six remarkable things about the sage:

- RE dwelling, the sage’s personal role would be:

- Not-Being efforting (as we discussed here). The pictograms for the word that means “dwelling” show someone staying at home at the tea table, chaste and unmarried, following something slowly from behind with tiger fur.

- RE practicing/moving on a public road, the sage’s teaching would be:

- just a husk of but not really speaking.

- RE the Ten Thousand Things… getting up and going to work here:

- “and yet now, bearded,” just a husk of but not really falling into some hollow-words style of governing that’s like a hand from above wielding that chisel used to mark slaves and criminals.

- RE birthing:

- “and yet now, bearded,” just a husk of but not really flesh-and-blood, meat-holding Being (as we discussed here);

- RE efforting:

- “and yet now, bearded,” just a husk of but not really expecting that will be holding one’s heart-core like one’s mother (shì).

- RE real work completing that final nail in the weapon on a pole:

- “and yet now, bearded,” not abiding (in fact, absent as sticks that were tied together to start a fire—pfft!).

- RE dwelling, the sage’s personal role would be:

- And here Lâozî jumps in to interject extra detail. Lâozî repeats the last point to tell us something more about, that is to say, this particular grown man with a hairpin and public courtesy name (fū) who’s absent as sticks that were tied together to start a fire, not abiding:

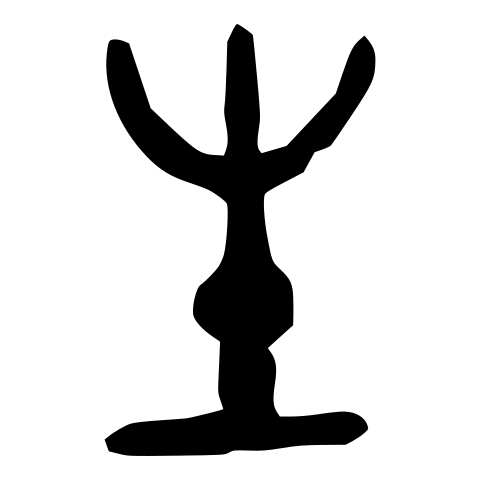

- the sun sees this particular non-abiding man is not really leaving, not really withdrawing like someone with a mouth or cave between their legs (qù 去). Here’s what that bronze inscription character looked like:

What a description of a life! That last big list began and ended with “efforting.” We learned that a sage’s personal role in dwelling is a Not-Being efforting. And by the end we learned that a sage might “effort” but isn’t really expecting anything personally of-the-heart to come from it (shì).This is important to remember since “efforting” comes up over and over again throughout the rest of the book.

The character shì (恃) combines the image of a heart with that of a temple or monastery. In Classical Chinese it meant mother, and now usually translates as rely on, presume upon, trust to. Dào translators call it take credit for, presumption, expect/expectations, lay claim to, claiming victory, claim as one’s own, claim possession, possessing, depend on, and return to. It’s like something has a hold on you, for better or worse. My translation, which I use in all three places where this character appears in the Dào, is:

expecting that will be holding one’s heart-core like one’s mother

~

I’m intrigued by what we’ve learned in Chapter 2 regarding: public opinion’s effect on what’s gestating, how that causes different pairs of “opposites” to mutually manifest, what Lâozî thinks that means for a sage’s life, and what happens in one particular man’s life who lives like that.

Actually, by “intrigued,” I mean that I have a lot of questions! Why does the sage “effort” at all? And why not expect a heart-level dependability from it? What can the sage—or we—trust will hold one’s heart’s claim? What’s the opposite of efforting? These are the answers I’m keeping my eyes open for as we move forward.

~

Does the final part of the chapter, describing the particular grown man’s experience, speak to these questions? Then the answer might be: do real work finishing things, but do it like a fire-starter… which means you won’t dwell there, and therefore you won’t ever really withdraw.

But, let’s face it, the old Lâozî-era image for that “withdrawing” character (qù 去) is very odd. Did you think I was just going to glide over that picture?! When I see a drawing of a man over a mouth-like opening and the dictionary definition withdraw, I think of a man just finishing or maybe interrupting sex. I can’t figure out if this is obvious or just reveals that I have the sophistication of a junior-high boy. But then some etymologists have described the image as “a man with a hole in his crotch.” Now that, to me, sounds like a woman passing/identifying as a man. And it makes me wonder. It makes me look back at everything we’ve read so far with a completely different question: was Lâozî a woman? When it occurred to me, I decided to keep this question in my mind as I went forward with the translation, and at the same time not be attached to it. We will delve into this more—much more. Meanwhile, other linguists have thought it could be a representation of a man’s anus and therefore mean “getting rid of” like “waste” (AKA pooping). Or others believe it might be related to a different Chinese character that shows a mouth next to a person (rather than below) and means “open one’s mouth,” possibly referring to the custom of saying goodbye when you leave some place. I also looked at other definitions of this word to see if we could get more clues. One is to play a part or character, to act. Another is last or past. A recently coined meaning for the word is what the hell, damn, fuck. Honestly, I couldn’t agree more! It’s baffling. And it kind of changes everything.

Maybe as we leave Chapter 2 we’re about to find out more about what it looks like to be as absent as the twigs that started a fire… not dwelling. And therefore not really withdrawing/leaving/passing/play-acting/past.

Once again, I ask: why the obscurity? Is it just too hard to clearly describe because it has to do with that ease-y extraordinary way of being that can best be described as the absence of so many of our typical hard-and-fast things and behaviors—an absence of the grind and the surface matters? Or is all this code for something else? Maybe both?! I vote for both.

Thanks for joining me here again. Next up: Chapter 3, where we learn a little more about this world of Lâozî’s before stuff starts to change pretty quickly in Chapter 4! Meanwhile, thanks for your questions, ideas, and comments. Please keep them coming. You can use the contact form to reach me anytime. See you next week!