wèi

“What’s in a name?” Sometimes I wonder if this isn’t Lâozî’s most pressing question in Chapter 1 of the Dáo Dé Jíng. Consider the different kinds of naming presented in this first chapter:

- public courtesy-names: Inside the cháng character, we learned that when young men go through a ritual to become a grown man, they get a formal adult name as well as a jīn head cloth to cover their topknot. Women also received courtesy-names.

- its personal, childhood name—what it whispers to identify itself by moonlight: This kind of name, míng (名), is what we in the U.S. would call your “given” name. It’s what everyone calls you when you’re a kid. In ancient China, after you received your adult, public courtesy-name, only your intimates would still call you by your childhood name and usually only in private. In the Western Zhou Bronze (WZB) script that I think Lâozî used, this beautiful character, was depicted by a pictogram of a moon:

- what it’s called—from the gut: Lastly, there’s today’s word-of-the day: wèi. Modern definitions are to say, tell, or call. In the Dào, it’s usually translated as name but also as called, means, says or, is. For this reason, the reader usually can’t tell when Lâozî uses wèi and especially can’t tell if Lâozî was writing wèi or míng. But I think the two have different significances. The modern way of writing wèi is this compound character:

謂

This is another case in which I can’t find an image of the compound character in WZB Inscription script, though I can find images from that era of each of the sub-components. Of course, I like to imagine Lâozî mashing things up to invent these words, but I must confess I haven’t done enough research to know if these words appeared in documents earlier than the Dáo Dé Jíng, so this is just fancy for now.

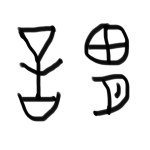

The left sub-component in today’s character is considered to be a person speaking with their mouth. The pictogram looks like a person coming up out of a mouth): ![]() The right sub-component is itself another compound character meaning gizzard of a fowl or stomach and inexplicably, at least to me, depicted by a drawing of a field above a moon:

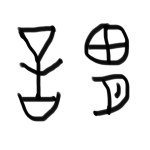

The right sub-component is itself another compound character meaning gizzard of a fowl or stomach and inexplicably, at least to me, depicted by a drawing of a field above a moon: ![]() This right-hand component also is pronounced wèi. For that reason, it’s considered to be a phonetic component that tells the reader how to pronounce the overall compound character. As you remember and will see again below, I like to include the phonetic part in my translation. You will notice however that I decided to stick with the established meaning—gizzard or stomach—and not specifically call out the sub-sub-characters because that starts to gets a little complicated even for me! I’m hoping this sub-character simply meant stomach to Lâozî, but who knows; maybe in the future I’ll explore the field/moon symbols.

This right-hand component also is pronounced wèi. For that reason, it’s considered to be a phonetic component that tells the reader how to pronounce the overall compound character. As you remember and will see again below, I like to include the phonetic part in my translation. You will notice however that I decided to stick with the established meaning—gizzard or stomach—and not specifically call out the sub-sub-characters because that starts to gets a little complicated even for me! I’m hoping this sub-character simply meant stomach to Lâozî, but who knows; maybe in the future I’ll explore the field/moon symbols.

So now you can see how I combined these components to hand-draw a WZB version of the compound character:

Initially, as you saw in this blog’s first post, I translated this as what it’s really called—from the gut. Because I thought the tendency of translators to stray into very confident, emphatic words—like is and means—combined with that “gut” image to make this form of naming seem more objectively true. I now think I may have gotten a little carried away (!) and have removed the word really. Now I’m using:

what it’s called—from the gut

But still, I do feel this kind of name’s somehow higher level than the very personal míng. Not better, just more universal.

What do you think? And what do you make of these three different kinds of naming all showing up in Chapter 1? Maybe it’s too early to tell, but somehow I don’t think there’s a lot of accidental coincidence in the way Lâozî puts characters together in a word, line, chapter, or book. Click on the comment icon in the header or use the comment form tab to let me know your questions, ideas, concerns, feelings, or experience with naming, here or in your own world.

Many thanks for joining me here—we’re close to the point where we can step back and look at Chapter 1 as a whole with all new eyes as to how the pictures there work together to… make a story… or lead us into the rest of the book.. or whatever it is we find they do! See you next time.

PS: Check out the new Dates, Dynasties, and Their Scripts tab if you’d like a simple timeline where you can see how everything dovetails together.

Last tinkered with 3/10/20.