yù

Things go better when we don’t confuse “desire” and “want”—whether in translation OR in our own lives.

- “Desire” is when something pulls you; you feel it. It moves you. In English, we describe the most essential such experience as our “heart’s desire.” Perhaps it IS always our heart pulling us when we feel that inexplicable longing to do something… to go somewhere, make something, or talk to someone. Whatever the action, like a river pulled by the invisible force of gravity toward its sea, desire always leads us into some movement, into falling into what pulls us… into the very next step.

- “Wanting” is when something’s missing and/or you think it is—it indicates a lack of something. This is a more unsettling feeling, not particularly an energizing feeling, but still a part of our human life and nothing to be ashamed of.

Both situations will occur in a human life, but how we feel is different as is our typical behavior and also… what would be most helpful.

Our word-of-the-day yù (欲) gets translated as both desire and want—often by the same translator. It’s also called wish which is something else altogether since it pulls in a wistful sort of request for supernatural help.

So, which of these options best represents yù? Let’s look at what the old scripts of Lâozî’s times show us in their pictograms.

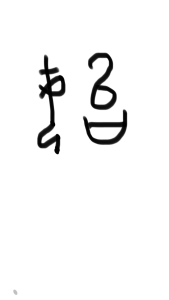

You can see right away that we’re dealing with a compound character. The left sub-component is considered the phonetic one that tells the reader how to pronounce the word, and I guess gû does indeed rhyme with yù. Gû‘s modern character is 谷, and the Western Zhou Bronze (WZB) inscription looked like this:

I’m relieved this looks so much like the left-hand side of the very first character I showed you above because that one’s written in the Warring States (WS) Chu Slip script that came just after Lâozî (check out the Dates, Dynasties and Their Scripts tab to follow that timeline). You know I prefer the Western Zhou Bronze inscriptions, but I couldn’t find any such version of the whole compound character. The similarity between the two scripts in this sub-component gives me confidence that the WS script is a good approximation of how Lâozî may have written this character. It depicts a stream running between two mountains and is translated as valley, gorge, ravine.

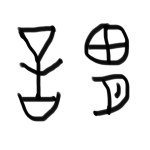

The right-hand sub-component, qiàn (欠) translates as to lack, be deficient, yawn. Depending on which linguist you listen to, it shows either a knife (⺈) or a mouth:

atop a person (人).

I have almost always lived in landscapes where ravines are commonplace—playing in them as a child, hiking them as an adult, and surveying and analyzing their dimensions and changes as a stream restoration hydrologist. What I’ve experienced is that a yawning, slashed, eroded gully has way more in common with what’s “wanting” than with “desire” or “wish.” Nonetheless, “desire” is so ubiquitous in others’ translations that I tried to incorporate it along with the pictogram in my own initial translation: desiring what’s wanting—what’s been eroded from this ravine…

~

Let’s try out my translation to see if Chapter 1‘s structure and content sheds any light on the subject. Both times our word yû occurs, it’s followed by these words:

this means:

keeping watch from the temple tower for

what it holds a basket of…

Here’s a quick breakdown of those characters:

~ yî, 以: This is a very common word in the Dào Dé Jīng. Its left component carries the meaning but remains a mystery. In the WZB it looked like this:

Some say it’s a plough; others say its a turned version of the symbol for a snake or a fetus. The right-hand component of the current character 以 wasn’t added until modern times. It’s a person, and in Western Zhou Bronze Inscription that looks like this:

We’ll see this character a lot as we go forward. The word yî is translated as by, by means of, according to, so, so as to, in order to, therefore and other connecting, almost causal or at least logically-linking transitional words. I fiddled with a lot of ways to make it work in all 46 contexts where it occurs in the first 37 chapters and came up with: this means… I don’t like that I haven’t included the pictogram itself, but the options are too different for me to decide on one yet. That could change in future posts as we learn about the sub-component’s use in other words and get a feel for it.

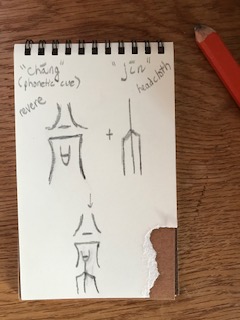

~ guān, 觀: In this compound character, the left side shows a heron. Its old WZB form is beautiful:

The right-hand component means watchtower, platform, or temple—it was drawn as an eye over a pair of legs:

This compound word now means observe, watch, see. I translate it as: keeping watch from the temple tower for…

~ qí, 其: Here’s yet another seemingly inconsequential word that’s translated many ways, usually something like its or has but also he, she, it, they, one, his, hers, theirs, that, those, probably, perhaps, therein… You know I do not like the predicament this creates, consistency-wise! The WZB inscriptions shows a basket on a stand:

After another chunk of time fiddling around for something that can work anywhere, I just went pretty much only with the image, as I think it says it all: what it holds a basket of… So does that mean “what the basket is made of” or “what’s inside the basket?” Hmmm. Either way, and with that double possibility, I think it’s in keeping with all the translation choices in the list you just read.

Look here at how all these words work together:

desiring what’s wanting—what’s been eroded from this ravine…

this means:

keeping watch from the temple tower for

what it holds a basket of…

It looks like Lâozî just straight-out gave us a clear way to interpret our word-of-the-day: when someone “wants” something, that’s saying they are looking for their own stuff. They feel like some of what their life holds—contains or is made of—is lacking, like the soil that was washed away to make a ravine. And when that happens to us humans, we very much do “want for” whatever basic ingredient we feel is missing—we maintain a sort of vigilance and sense of lack. Lâozî’s words definitely make yù sound like it’s more about what’s missing than about being pulled toward a heart’s desire or making a wish.

That decides it. I’m changing my translation. Mixing this word up with desire is unnecessary and misleading. We don’t want to mislead ourselves into thinking that any further information Lâozî gives us about wanting is pertinent to desire. Bonus: my new translation’s simpler, and it still can be used as either a verb or a noun:

wanting (what’s been eroded from this ravine)

~

So what else does Lâozî teach us about wanting here? You’ll remember that just before this section, Chapter 1 introduced us to two seemingly opposite or complementary characters Not-Being and Being. Specifically, in this first use of them, Lâozî linked them up with míng (personal childhood name) to explain that “Not-Being míng” and “Being míng” are each the origin of something… something unique for each one.

Names as an origin? That puts me very much in mind of quantum physics as well as the thought-provoking psychologic, neurolinguistic, and anthropological research indicating that if we can’t name something, we can’t really develop our perception or understanding of that thing. And as we learned in a previous post, both approaches to naming are the origin of cool stuff: Not-Being, its name is Sky-Earth’s beginning like conception in and by a woman; Being, its name is all the manifest stuff’s nourishment like being suckled by a woman.Very cool. But there’s more.

Lâozî says there’s something that’s followed logically for many generations…

Here’s where learn about exactly what might be “wanting” in two different aspects of experience. Before getting specific, Lâozî specifies that we’re now talking about the timeless, constant, ever-present version of it all—as represented by the traditional “you’re-officially-an-adult” males’ head-cloth.

Then, Lâozî tells us what “wanting” means for 1) the timeless mens’ head-cloth version of “Not-Being” wanting and 2) the timeless mens’ head-cloth version of “Being” wanting. Here’s my summary, in table form:

STATE, QUALITY, ASPECT, OR PERSONA:

Not-Being—————-> ————————–

Being———————> —————————

This “personal naming” is the origin of:

Sky-Earth’s beginning, like in and by woman

10,000-external things’ suckling, like being fed by a woman

In “timeless/head- cloth way,” wanting /looking for:

mysterious feminine essence

delineated surface

This makes sense. If “Being, its name,” at the most intimately known level, nourishes and rears the myriad of manifested things out in the world, then it follows that “Being wanting” also would have to do with this concrete kind of stuff. We know when something’s wanting, it will involve looking for the stuff IT HOLDS or IS MADE OF, and in this case, Lâozî says that’s going to be a clearly-marked outward surface. As you remember from when we broke down that word in a previous post, this is a feature that was defined by drawing a sword tip left to right. In mathematics/geometry/physics, such a lined-out surface is a plane—a 2-dimensional feature. The surface is what we see of the universe—of what exists. It’s obviously an important, vital part of our lives. In fact, it’s usually what we pay attention to. Lâozî says that in the eternally constant grown-man-head-cloth version of Being wanting, what we’re missing and keeping an eye out for is that surface plane. This seems correct and like the useful thing to do.

And Lâozî also reminds us of another part of our experience: something more mysterious and hard to describe or touch. It’s not concrete, and indeed Lâozî describes it as an absence. “Not-Being, its name” gives us the very beginning, the Source, or what some call the Divine, Sky-Earth, heaven. And when considering this “Not-Being” in terms of “wanting,” Lâozî says the stuff missing is mysterious feminine essence. That’s what it holds a basket of.

~

Wait. How can Not-Being Wanting be missing anything at all?

Here’s where we get a clear notion that Not-Being Wanting isn’t the same as not wanting. If it were simply “not wanting,” then that might be pleasant (or even noble in the eyes of a puritanical interpretation that confuses wanting with desire and desire with lust or greed). But nothing would be missing. And yet here we are with something missing, albeit a non-concrete mysterious essence of a something.

What exactly is this “Not-Being?” And if it’s something other than a simple modifier meaning “not,” then what does that tell us about its complement, “Being?” Is that something other than just a confirmation that something’s happening?

Review the tortuous logic I took you through in this post! Now you’re seeing why I did it this way for myself originally and why I laid it out for you here. I wanted us to follow exactly what we’ve read thus far about the nature of these Being and Not-Being characters. The structure I outlined in the table above is exactly how it’s laid out in Chapter 1… and it’s exactly parallel for Being and Not-Being. I’m pretty sure it drives us to the conclusion that Not-Being is as much of a something as Being.

Of course I don’t have an answer for you as to what these two terms mean. They’ve been the source of discussions about the Dào since… ever since this text was written as far as I can tell. But somehow I felt relief in clarifying for myself and you that they indeed are not simple little modifiers. There is something going on here. It’s baffling and disorienting. And that’s perfect.

Let me skip ahead for a minute to Chapter 3. There Lâozî comes right out and describes the Sage’s strategy in dealing with civilians — in “governing” them or rather, in the literal old images I prefer, “harnessing the river happy!” A fundamental step in the strategy is to create confusion—”Not-Being sure.” Ha! I would say Lâozî’s succeeding at that with this entire book! At least thus far. In the end of Chapter 3, and increasingly clearly all throughout the rest of the book, Lâozî shows us how this strategy leads to a deep rightness.

We have to unlearn some things to learn other new things. We have to get baffled to crack open enough to take in something bigger than we previously held, to increase our capacity. So I’m going to keep trying to suspend you and me in uncertainty. We can do it. We can tolerate it. We can even enjoy it. We’re built for this.

~

Whatever they are, the egalitarian structure of this chapter indicates that the not-so-visible “Not-Being” name/wanting is equally as important as the concrete “Being” version of those things. Lâozî even clarifies that these two parts are “a matched pair, like a harness of oxen yokes” presumably pulling things along nicely and evenly when they’re both involved.

Moving along forward… that’s where your life is happening. The Dào has a lot to tell us about living with and from and for the heart—that’s the stuff of desire and movement. Lâozî devotes the entire second half of the Dâo Dé Jīng specifically to that straight heart path (AKA the Dé or Te), and there’s lots of information on it coming up in this first half also. Until then, when you feel your heart pulling you somewhere, take a step.

But today’s word is about the inevitable times when we feel ourselves not moved to move but like we’re sitting up on a watchtower, staring out over a valley because we feel we’re lacking somehow. Thats part of being human. And then it is fine to keep a watch for what’s missing. It helps to know what you’re looking for though. Sometimes it will indeed be the surface stuff—specifically it will look like a boundary, a line drawn with the tip of your sword. That’s true whether you consider yourself a sword-bearing frontiersman on patrol (remember that was part of the original image) or not. And sometimes it will be a mysterious feminine mist of an essence—that’s true whether you’re a man or woman. When your wanting isn’t very definable—you can’t figure out what or how to draw a boundary or address the surface or even see it and so you keep watching and waiting and watching—then feel around for an essence and breathe it in. We’ll get more specific instructions as we work through the book, but honestly it just comes back to that.

Thank you for joining me in floating in—heck, diving into—Not-Being sure. I’ll see you tomorrow.