fū

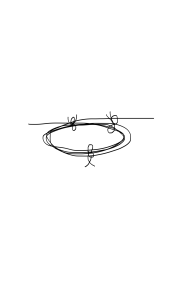

Chapter 2 introduces another character that shows up in pivotal times throughout the Dào: (夫). The Western Zhou Bronze Inscription starts with an image of a man…

… and adds a hairpin (一):

I don’t know for sure if this image has to be male or if that’s just how it gets translated now. Women also wore hairpins, but maybe this image shows the pin men wore after their Guan Li naming ceremony when they officially became an adult man. Modern translations of this character when it’s pronounced fú are just that: male adult, man; husband; person; manual worker.

But there’s another pronunciation of this same character: fū. That’s how it’s usually been transcribed in the received versions of the Dào Dé Jīng. Its modern translations are as a generic personal pronoun—he, she, it, they—or a particular “demonstrative” pronoun like this, that, these, those. Translators of the Dào also interpret it variously as you, for, just, because, this very, the, ones, people, that is, and only. A lot of times it’s somehow combined with words like therefore, and, so or other introductory or transitional words or just dropped altogether and considered to be a meaningless particle. Perhaps, the translators think it’s been added for rhyme meter, and alliteration.

The thing is, its unique status as a particular character is lost when we do that. So, as you know, just in case it meant something to Lâozî, I give each character a unique translation that includes its pictogram image and can be used in every instance it occurs. For 夫, I have come up with:

that is to say, this particular grown man with a hairpin and public courtesy name…

Notice how it includes both of the key themes we saw in our summary of Chapter 1: hairstyles and naming types!

~

This particular grown man character is introduced to us in Chapter 2, just where we left off upon learning that when it comes to real work completing, the grounded sage, as one bearded, is absent as sticks that were tied together in a bundle to start a fire—’fff!’—not abiding or dwelling where birthed. Immediately after that line, Lâozî specifies:

That is to say, this particular grown man with a hairpin and public courtesy name…

essentially and only—like the heart of the ‘short-tailed bird’—

“absent as sticks that were tied together in a bundle to start a fire—’fff!’—not

abiding—dwelling where birthed…”

the sun—walking across the sundial a while, stopping a while—sees indeed

this means:

the husk of the initial protective bud casing—the sepal—but not really the true inner flower of

withdrawing like a person with a mouth or cave between their legs—leaving.

This is the particular format in which we most often see the 夫 character used: after a list describing various aspects of someone’s situation. After a list, Lâozî highlights one of the list’s conditions by repeating it and referring to this particular man to whom this applies. And then Lâozî reaches a conclusion about that particular man.

In this case, Lâozî says that the particular grown man who’s completely “not there” when it comes to abiding is “not really leaving.”

In other words, this guy who never stayed isn’t really going away. Makes sense. You could say this particular person already has left—like a bundle of twigs lit to start a fire, “Pfft!” It gets things going at the beginning, and then is gone. This character, rather poetically, is also pronounced fú but with a rising tone. Its pictogram shows two sticks tied together, which you can still see in the modern character: 弗. (An alternate explanation is that they are two bent arrows tied together to be straightened. Either way, its usage is dialectical and not commonly used now. It’s most often translated as “not,” but our friend bù is much more commonly used as that kind of negative particle.)

~

Have you ever felt like that bundle of twigs? You start the whole thing, and that’s your contribution. Maybe intentionally, that was your plan, or maybe the feeling of being “used up” came as a surprise to you. Maybe no one notices you’re not really there anymore. I can imagine this feeling bad—like “burnt out” or even taken for granted. But also I can see it being fine—like you’re a pivotal, essential “fire starter” and not part of the ongoing cooking or heating or whatever.

What’s the difference between these two versions? And more importantly: what do you do now? How we frame what happened—our mindset—is going to matter.

~

All this talk of leaving puts me in mind of the fact that, legendarily, the Dào Dé Jīng was imparted to a border guard as Lâozî departed from the country. Perhaps Lâozî is self-revealing something here. Perhaps Lâozî’s not really leaving—maybe because Lâozî wasn’t even still there to begin with.

As we go, let’s be on the lookout for more clues about Lâozî’s story and experience of it as well as maybe some insights on how we can frame our own experiences in not-really-leaving somewhere because we left long ago. Thank you for being here with me—please use the Contact form to send me your responses. See you next time!