tiān

You’ve seen the word Tiān many times—as part of the word Tiananmen, The Gate of Heavenly Peace, in Beijing. Actually, we’ll see all three components of that word in the Dào Dé Jīng, starting with today’s word: tiān. It’s the heaven part, and its modern character looks like this:

天

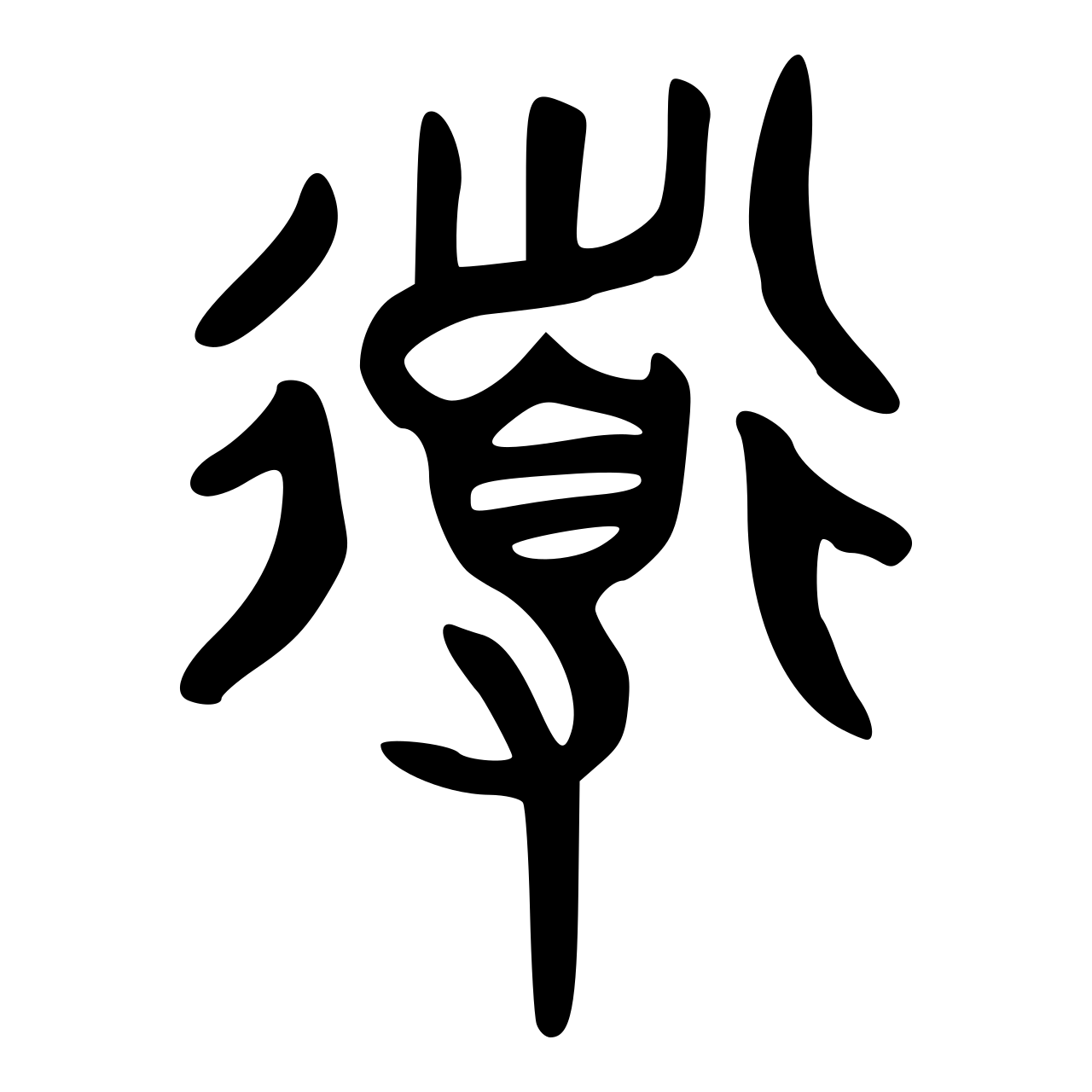

In the pictogram of the Warring States Chu Slip script—which is the era after Lâozî—as well as every script thereafter, this character’s shown by a picture of a person with a line over their head:

In the oldest known Chinese writing—the Oracle Bone script of the Shang dynasty, it also looked like that:

During the Zhou dynasty, this figure for sky was the word that became used to talk about the highest god which previously was called Shàngdì, meaning something like God of Shang. That’s why some people occasionally translate tiān as Lord, presumably depending on context. Why the change in the Shang dynasty? One thing I’ve learned is that often with each new emperor, words that sounded like the last emperor’s name were more or less banished! It really complicates etymology. Sometimes I try to make some big cosmic reason for a character turning into or being replaced by another character, and it turns out that no one was allowed to say the old name, for example “Shang,” lest the powers-that-be-think they’re not loyal. Obviously I am over-simplifying, Anyway, in Zhou times, this high god and/or the place it lived were called Sky, so that flavor often is captured by translating this word as heaven. “Heaven worship” is one name for this religion which was the state religion before the 20th century. Its philosophies are quite beautiful sounding:

“…it sees the world and the gods of its phenomena as an organic whole, or cosmos, which continuously emerges from a simple principle. This is expressed by the concept that “all things have one and the same principle” (wànwù yīlǐ 萬物一理).This principle is commonly referred to as Tiān 天, a concept generally translated as “Heaven”, referring to the northern culmen and starry vault of the skies and its natural laws which regulate earthly phenomena and generate beings as their progenitors.“

Yes, I just quoted Wikipedia! Sorry/not sorry because when you want to know just a little about something, it is just the way to get a taste.

I want you to see how, in Taoism, this word Tiān is a fundamental concept with all kinds of the cosmological implications we just tasted. But the question is, was Lâozî a Taoist?! If you think Lâozî founded Taoism, then that’s like asking if Christ was Christian (we can be sure Jesus wasn’t attached to later dogma in the Christian church since it didn’t exist yet, though people can and do argue as to which of those dogmas are exactly as he meant it to be). Whether or not you think you think Lâozî founded Taoism partially depends on if you think Lâozî lived in the 300’s or in the 500’s. Why does this matter to me right now? Because I’m trying to figure out if Lâozî used tiān as heaven or sky. Probably both, like current English speakers do with the word “heavens.” Its use as capital-H Heaven was clearly established during Lâozî’s time, and that’s probably why almost every translator calls this character heaven. This creates such a quandary for my picture-oriented translation method! Dang it. I’m going to change my translation AGAIN. And it’s going to be longer. Again:

Heaven (that sky level above the human head)

“Remember,” I keep telling myself, “we’re going for the complete picture, not the most succinct one.” And you know what? I think the complete picture ends up being super evocative and even lyrical.

~

Before we leave today’s word, I want you to know a little about all the ways Lâozî combined it with other characters in the Dào Dé Jīng to create distinct meanings.

- tiān xià: During Lâozî’s lifetime, xià (下) was drawn as one line below another:

It now means lower part, under, inferior, and below. I capture all that with my interpretation of it as down below (lower level). As we’ll see beginning in Chapter 2, this word is commonly combined with tiān to make Sky-Below or Heaven-Below. You can see why most translators interpret it as world, and, in different places, everyone, all in the world, etc. I of course let the lengthy combo of my own translations stand on its own, but I do hyphenate them since they’re so commonly combined into one entity: Heaven (that sky level above the human head)–down below (lower level). When you look at it like that, does it mean heaven when it occurs down below? Or does it mean some scope that encompasses both levels? We don’t have to decide. As usual, we can let the poet’s multi-layered meanings wash over us.

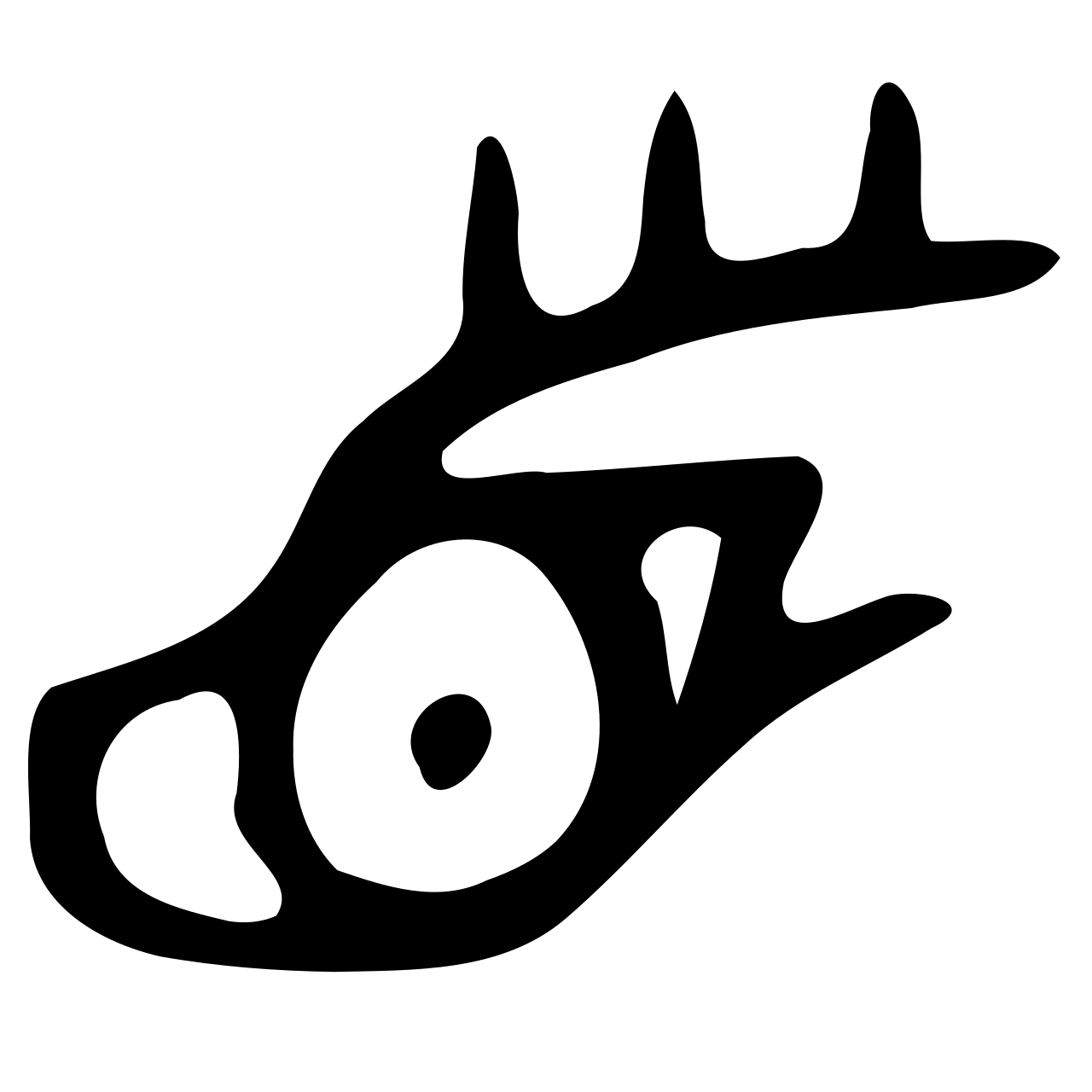

It now means lower part, under, inferior, and below. I capture all that with my interpretation of it as down below (lower level). As we’ll see beginning in Chapter 2, this word is commonly combined with tiān to make Sky-Below or Heaven-Below. You can see why most translators interpret it as world, and, in different places, everyone, all in the world, etc. I of course let the lengthy combo of my own translations stand on its own, but I do hyphenate them since they’re so commonly combined into one entity: Heaven (that sky level above the human head)–down below (lower level). When you look at it like that, does it mean heaven when it occurs down below? Or does it mean some scope that encompasses both levels? We don’t have to decide. As usual, we can let the poet’s multi-layered meanings wash over us. - tiān mén: As you probably intuited at the beginning of this post, mén (門) translates as gate. The old glyph has barely changed:

I love it when that’s the case. It is quite simply a drawing of a double-winged gateway, and that’s how I translate it. Combined with tiān, we get: Heaven (that sky level above the human head)–double-winged gateway. Usually other translators call it heaven’s gate, gates of heaven, or heavenly gate.

I love it when that’s the case. It is quite simply a drawing of a double-winged gateway, and that’s how I translate it. Combined with tiān, we get: Heaven (that sky level above the human head)–double-winged gateway. Usually other translators call it heaven’s gate, gates of heaven, or heavenly gate. - tiān dì: Right here in the first chapter we see one of the most common uses of tiān: it’s combination with dì (地). Lâozî most likely would have drawn dì like this:

The left side of that character, by itself, looked like this:

The left side of that character, by itself, looked like this:  That’s a lump of clay on a potter’s wheel and means earth, soil, clay, dust. The right-hand side of dì is considered the phonetic side, though as is often the case, that seems like a stretch to me… this sub-component’s pronounced yê. How does that tell us how to pronounce dì? As usual, I suspect the so-called phonetic component also contributes to the meaning. There’s a lot going on in that right-side, and I’m still trying to figure out all the little sketches in there, but apparently in Lâozî’s era, it was drawn more simply, just with this:

That’s a lump of clay on a potter’s wheel and means earth, soil, clay, dust. The right-hand side of dì is considered the phonetic side, though as is often the case, that seems like a stretch to me… this sub-component’s pronounced yê. How does that tell us how to pronounce dì? As usual, I suspect the so-called phonetic component also contributes to the meaning. There’s a lot going on in that right-side, and I’m still trying to figure out all the little sketches in there, but apparently in Lâozî’s era, it was drawn more simply, just with this: There’s been a difference of opinion on whether this was a pictogram of female genitalia, a washbasin or funnel, or a mouth with air coming down out of it. It’s translated as too, also, and as well or as neither/either in the case of negatively phrased sentences. In other words, it’s a sound you make to add emphasis. Where it occurs by itself in this book, I’ve naturally translated it as —yes, that too, vagina! Of course, you know by now that I’m not intentionally being provocative just on this character since I throw in the whole kitchen sink on every, character, yê?! And too, you may be seeing a trend where over time characters’ seem to have undergone some puritanical “cleanups,” at least in the English translations. We see that with English words too. Some still reference their very earthy origins and we don’t even notice it when we say them. For example. when things are messed up and you say there’s a “snafu,” you may not know that was a military acronym for “situation normal: all fucked up.” So for now we’ll assume all these missing references to women with breasts, nursing women, etc. are probably normal and not an effort to sanitize or gender-wash the Dào. Nonetheless it may feel profane to some that I’m reintroducing these old words and images into a sacred document. Please know, I truly don’t think of it that way as I consider none of this profane and furthermore consider it an honor to Lâozî to try getting close to the original writing as best we can. And of course, most importantly, nothing I or anyone can do is able to diminish the Dào or the Dào Dé Jīng. And with that big disclaimer… my translation of dì is Earth (this soil vagina). Altogether with tiān, we have: Heaven (that sky level above the human head)—Earth (this soil vagina). Or you can silently say in your mind Heaven-Earth or heaven and earth, as most translators do.

There’s been a difference of opinion on whether this was a pictogram of female genitalia, a washbasin or funnel, or a mouth with air coming down out of it. It’s translated as too, also, and as well or as neither/either in the case of negatively phrased sentences. In other words, it’s a sound you make to add emphasis. Where it occurs by itself in this book, I’ve naturally translated it as —yes, that too, vagina! Of course, you know by now that I’m not intentionally being provocative just on this character since I throw in the whole kitchen sink on every, character, yê?! And too, you may be seeing a trend where over time characters’ seem to have undergone some puritanical “cleanups,” at least in the English translations. We see that with English words too. Some still reference their very earthy origins and we don’t even notice it when we say them. For example. when things are messed up and you say there’s a “snafu,” you may not know that was a military acronym for “situation normal: all fucked up.” So for now we’ll assume all these missing references to women with breasts, nursing women, etc. are probably normal and not an effort to sanitize or gender-wash the Dào. Nonetheless it may feel profane to some that I’m reintroducing these old words and images into a sacred document. Please know, I truly don’t think of it that way as I consider none of this profane and furthermore consider it an honor to Lâozî to try getting close to the original writing as best we can. And of course, most importantly, nothing I or anyone can do is able to diminish the Dào or the Dào Dé Jīng. And with that big disclaimer… my translation of dì is Earth (this soil vagina). Altogether with tiān, we have: Heaven (that sky level above the human head)—Earth (this soil vagina). Or you can silently say in your mind Heaven-Earth or heaven and earth, as most translators do.

~

The sky just above your own head—the fresh air, the perfect oxygen level, the way it renews you not just to breathe it in but to look up at it. No matter your religion, it is heavenly. That, I think, is my favorite part of today’s word, of where I live, and of most days. I hope you have some time today to lift your eyes and breathe in this heaven that we have access to everyday. Thank you for using part of it to join me here.