Mín

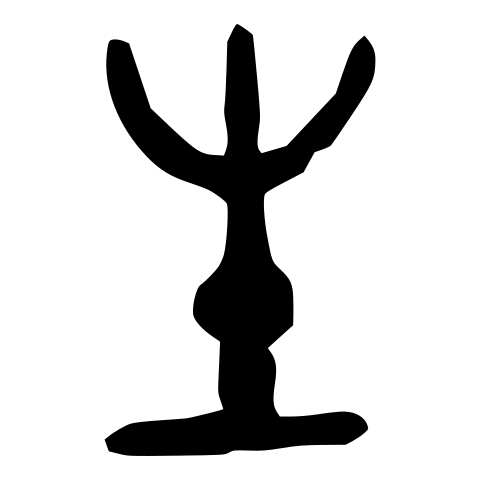

An eye pierced by a dagger. That’s the pictogram for today’s word, 民, which is modernly translated as people, citizens, folk, popular, and civilian.

Wow. This is why the images within the characters matter to me. The above picture of an eye and dagger is what Lâozî most likely would have drawn while writing down the 37 chapters we now call The Dào. Eye-piercing was an historic method for enslaving people. I’ve read that this practice was associated with enslaving the Mín people, hence this word and their name. Words from the Mín dialect make their way into the Dào in several places that I’ll note as we go along. We saw our first one in the last post, and—possibly not coincidentally?— that word (shî) occurs directly before today’s word (Mín) the first four times we see either one used.

As you recall, Chapter 3 opens with a list of three attitudes to avoid. If you avoid these, then you have a populace that doesn’t do three corresponding bad things. –>Not really elevating the elite rich means people don’t really compete (like with two hands clawing over a plow). –>Not really treasuring hard-earned transformation of riches means people don’t really “effort” thievery. –>And not really seeing something as definitely wanting or missing means peoples’ hearts aren’t really in a confused anxiety where their tongues are like twisted threads with one remnant string hanging out.

But, to be specific, each of those three prohibitions is spelled out according to this formula:

Not really doing [fill in the blank]

is breeding (like a gentleman holding a fountain pen)

civilians (like the Mín people enslaved by blinding with a dagger)

who don’t really do [fill in the blank].

I found this to be a nice time to re-read our last post and really reflect on that image of a government official holding in his hand a “fountain pen” that resembles “a flagpole sticking out of a drum.” Remember too: this image possibly shows that tool superimposed over a mouth. And of course there was the charming information that its meaning—to make someone do something—means to f*@# in the Mín dialect. So is it just me or does it sound like “breeding civilians” is another way of saying f*@#-ing the lowly masses who were enslaved by blinding their eyes with a dagger.

Does my heart suddenly seem rather dark to you?! Okay before I get all carried away seeing something horrible where it doesn’t exist, let’s find out what happens in the rest of the chapter and how these two words (shî mín) are used there. After all, this chapter is actually the only place that this shî character’s used at all.

~

What immediately follows is another instance of Lâozî telling us the suns sees indeed that this means something about the grounded sage. In this case, that description of what breeds civilians to be a certain way means the grounded sage has a particular style for governing (zhì, 治).

If you look at this modern character for zhì, you see it has two sub-components. The left side evolved from the pictogram from water:

The right-hand sub-character (台), when it’s by itself, is pronounced yí in Mandarin and was the original form of the word for happy or pleased. It depicts a mouth (the square) below another character. Most often that arrangement of a mouth means speaking about though sometimes it actually does seem to carry the meaning of a mouth, a cave, or a similar type opening.

In this case the mouth is drawn below a character that’s sometimes thought to be a plow or a symbol for turned or revolving. More often, and more specifically, it’s thought to be a variation of yî (以) which we investigated in a previous post. There I translated it as already… finishing it in the womb based on its typical translations and the original pictogram which is said to be either a snake or a fetus. Nowadays, when this character’s combined with the mouth character to make yí, it seems to refer to some aspect of talking about oneself. The result’s translated as I or me or sometimes as what. It no longer carries the original meaning of happy/pleased, harmony, or joy unless it’s combined with a character showing a heart to the left of it: 怡.

When that same happy character was combined with the pictogram of water to form 治, the resulting meaning was often an ancient river name (pronounced either yí and chí). In modern usage, though, it’s pronounced zhî and translated as to govern, regulate, or administer. Historically it was used to describe a seat of local government. Dáo translators generally prefer the terms govern, governing, and government, but sometimes you’ll also see them translate it as rules or leads. Here’s how I translate it to include all the imagery:

governing—regulating by harnessing the river named Happy or speaking of turning yourself—

I know it gets kind of wild when I translate this way, but I do so love the results. I love how it associates harnessing the River Happy with regulating or turning yourself around…. and with governing.

UPDATE: I look into this character a little more in a later post here.

~

So, to continue on, Lâozî says that in light of that list of what kinds of attitudes do or don’t breed what kinds of civilians, a sage’s governing looks like this:

The sun—walking across the sundial a while, stopping a while—sees indeed

this means…

the grounded sage—listening and speaking, standing connected to earth as well as the heavens,

that person

has this

governing—regulating by harnessing the river named Happy or speaking of turning yourself:

~ emptying—like lifted land…

what it holds a basket of…

heart-core…

~ really filling—like a building with strings of solid cowry-like riches…

what it holds a basket of…

inside—the gut, the meat belly;

~ being as fragile as a matching pair of decorative bows or little wings…

what it holds a basket of…

having heart-core determination and aspiration

~ strengthening like an insect—turning yourself as a venomous snake-like bow…

what it holds a basket of…

that bony will that comes from a skeleton framework.

What “it” is referred to in the phrase “what it holds a basket of?” This character, qí (其) puzzles me. We first looked at this little connecting word back in one of our earliest posts. But when translating Chapter 3, I decided to go back and review all 61 times it occurs in the first 37 chapters of the Dào Dé Jīng and compare how it’s handled by different translators (especially Chinese translators). I ultimately decided it’s safe to say that this phrase doesn’t necessarily refer back to the word right in front of it. Rather it points the reader back to the most recent “subject.”

In other words, Lâozî probably isn’t saying that “emptying has heart-core.” More likely this phrase says that the sage’s governing empties the sage’s heart-core, fills the sage’s inside/gut, is fragile in the sage’s heart-core determination, and strengthens the sage’s bony will. However only Chia-Hsu Chen translates it this way.

Most translators say the sage’s govern empties the people’s hearts, fills their bellies, weakens their ambition, and strengthens their will. They think “it” refers back to Lâozî’s previous “paragraph.” Other translators leave out the whole question of whose basket is in question! They say the sage’s governing empties the heart, fills the belly, weakens ambition, strengthens will.

What bothers me is that these approaches aren’t consistent in how they decide what the connecting word qí is pointing to. And when you read the different options I pose here, this subtlety really makes a difference, doesn’t it? Maybe this is another example of Lâozî the poet being intentionally ambiguous. Maybe “it” could be any of those things. “It” could be the sage, the governing itself, the people, or it could even be the word right in front of “it.” Maybe it COULD mean “emptying has heart.” (I like that last version a lot. I translated it that way myself until I more thoroughly analyzed qí.)

So why do I belabor this?

Because it makes a difference on a very important point: does the sage’s way of governing have anything to do with making the civilians be a certain way? It’s easy to assume so. After all we usually do think of governing as controlling others. And in the first part of this chapter, we just saw some gentleman a fountain pen was making them do stuff. But it seems to me that the point of this next section here is that the sage doesn’t do that. Maybe the sage is just over here minding the sage’s own heart, gut, ambition, and will. The very particular way that Lâozî drew the “governing” character could support that—governing could be about turning yourself, harnessing your own Happy river.

Let’s see where else Lâozî goes with these topics in this chapter. It’s pretty interesting.

~

As you remember, in the very first sentence of Chapter 1, Lâozî set up a conflict between the definitive “kê” version of things and the cháng version—the ever-present traditional, timeless, constant version of things as symbolized by the head cloth that men donned upon becoming official adults. Now we learn more about the cháng (常) version. We’re going to learn about what happens with that traditional version of breeding civilians:

The ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—what we know as the timeless, whole head-cloth ‘ji’ version of

breeding—like a gentleman holding a fountain pen making something happen—

civilians—like the Mín people enslaved by blinding with a dagger:

~ nothing—no one dancing with long tails flowing from their wrists—nope, never, no way, nowhere, nohow Not-Being…

firing arrows from the mouth—sure;

~ nothing—no one dancing with long tails flowing from their wrists—nope, never, no way, nowhere, nohow Not-Being…

wanting what’s been eroded from this ravine

We know two things about the traditional version of breeding civilians:

- Not-Being… sure

- Not-Being… wanting what’s missing

Does this mean the traditional version of breeding civilians breeds civilians that aren’t sure and aren’t wanting or missing anything? OR that in the traditional version of breeding civilians, someone who is a Not-Being is sure and is wanting something that’s missing? It’s our old familiar debate about the nature of the shamanic dancer Not-Being character, wú, and the meat-holding character we call Being, yôu. Are they people or are they negative and affirmative parties? Does it depend on context? Let’s keep reading with an open mind.

When we do so, we see in the very next sentence Lâozî tells us a third thing about the traditional version of breeding, and this is for sure about this particular man with a hairpin and public courtesy name (fú). We met this character in Chapter 2. There we learned he was absent and therefore not really leaving. Here we learn that he’s a person who, in the traditional version of breeding, is sure:

breeding—like a gentleman holding a fountain pen making something happen—

that is to say, this particular grown man with a hairpin and public courtesy name…

“firing arrows from the mouth—sure” as the sun, daily

—now this is cooking!—

the husk of the initial protective bud casing—the sepal—but not really the true inner flower of

daring—lightly hitting ears on both sides of the head—

efforting—like lifting up an elephant,

—yes, that too, vagina!

~

All right, all right. Before I continue, I want to address the elephant in the room—and no, I don’t mean the actual elephant we once again see inside the image for “efforting!” I mean that last exclamation and its reference to female genitalia. Is this gratuitous sensationalism on my part? You tell me. I will give you the facts… in our next post. Because this one’s getting soooo long, and I want to tell you about all of Lâozî’s colorful interjections at one time.

Until next time, be sure to use the contact form to send me your questions and comments. Thank you for being here!