dé (德)

Right in the first chapter, we became aware of a hard-to-see dark structure—like a figure-eight skein of string-dyed-black (xuán). It underlies the true name of the matched pair of Being and Not-Being when they’re together… before stepping out of the cave and acquiring different personal childhood names. And then that hard-to-see dark structure of a figure-eight string dyed black, in turn, has a hard-to-see dark structure of a figure-eight string dyed black. And that—the whole arrangement?—is mysterious feminine essence’s (miào) double-winged gateway.

Now in Chapter 10, we learn more about this mysterious dark structure. And we learn about it in the context of our hero receiving an assignment to complete a task. The previous chapters have led up to this task nicely. Here’s what we learned before:

- Chapter 7: Heaven-Earth is now long-lasting and “capable of lengthy birthing” and that means

- the sage’s pregnant self, now bearded, is surviving and

- the wings are broken off of Not-Being’s disastrous personal concerns, and therefore Not-Being’s capable of completing personal concerns [non-disastrous ones, I presume].

- Chapter 8: Regarding higher-level ruling traditional virtue:

- “Someone” says that now bearded, you’re not really competing. [I assume that’s continuing the explanation of how the sage is avoiding disastrous personal concerns.] And we learn that this is very close to The Way.

- There’s a list of what I assume are the non-disastrous things that are of concern to you: abiding, heart core, speaking, being straight upright, one’s personal role, and laboring. And there’s a corresponding description of what each of these looks like to traditional virtue. In the end, our narrator re-emphasizes that this particular man who’s essentially and only not-competing is therefore, by logic, Not-Being in particular. And possibly this Not-Being has been made lame by resentment and blame. Resentment and blame on the part of themselves or of someone else, like traditional virtue? It’s delightfully ambiguous as usual.

- Chapter 9:

- If you, now bearded, are over-doing things, then it’s not really going to be helpful:

- You’re not going to be finishing what’s in the womb, not long safeguarding a child, not capable of defending your place… you will leave behind you only calamity.

- Alternately, if one’s pregnant self withdraws after real labor’s completed, then that’s Heaven’s Way of the loose-haired chieftain, walking awhile, stopping awhile, listening, and speaking of it all. That’s exactly The Way.

- If you, now bearded, are over-doing things, then it’s not really going to be helpful:

And now here, in Chapter 10 someone lists what I assume are the very real specific, almost paradoxical details of exactly following The Way. And then they challenge, “pah, can you?!“

- Can you carry the physical soul and spiritual soul bundled up into one… with being separated from Not-Being?

- Can you control chi or breath of life and cause softening… with an infant son?

- Can you do the washing and arranging for moving me to a new mountain posting and have the hard-to-see dark structure that’s like a figure-eight skein of string-dyed-black reflecting like a vessel looking down—all eyes—overseeing… with Not-Being ill on a stretcher?

- Can you love the civilians and regulate this nation by harnessing the river Happy and regulating yourself… with Not-Being very sure every day?

- Can you unlatch Heaven’s double gateway and shut it—like a person with a mouth between their legs withdrawing and covering an empty chalice from within the double-winged gateway… with efforting femaleness?

- Can you be as bright as dawn rising on a crescent moon—enlightened—and have hundreds arriving in all four directions like little lambs… with Not-Being very sure every day?

You can see the verbatim text here, and go here to read others’ traditional translations that leave out all the imagery from the old script. But you have to admit, it’s crazy how much that imagery has to do with having a baby, yes? And how it would fit exactly with my theory that our hero is a pregnant Not-Being—a shamanic woman—posing as a man? She’s trying to do all the impossible things involved in being a pregnant woman while also being a government official. It’s a lot.

The narrator concludes by saying there IS one example of doing all this stuff at once. It comes from nature:

Birthing—a bud sprouting from the ground

has this;

rearing animals—giving them feed from a bag tied with a rope

has this.

But for our hero to do it all? The narrator sums up that situation:

Birthing—a bud sprouting from the ground—

and yet now, bearded, you…

the husk of the initial protective bud casing but not really the true inner flower of

Flesh-and-blood, meat-holding Being;

efforting—like lifting up an elephant—

and yet now, bearded, you…

the husk of the initial protective bud casing but not really the true inner flower of

expecting that will be holding one’s heart-core like a mother;

lengthening like long hair,

and yet now, bearded, you…

the husk of the initial protective bud casing but not really the true inner flower of

dominating—like the house of that chisel used to mark slaves and criminals.

Our narrator gives our hero, or maybe us, a hint as to how to simultaneously rule and birth while not really a Being:

The sun—walking across the sundial a while, stopping a while—sees indeed

what it’s called when speaking from the gut…

the hard-to-see dark structure—like a figure-eight skein of string-dyed-black…

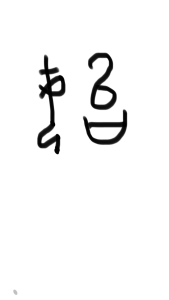

the Dé—an Ethics system that’s the straight-heart-core of the way.

The Dé is the famous subject of the second half of the Dào Dé Jīng (Chapter 38 through 81). It’s considered to be a set of principles for application of the Dao, for living according to The Way. And it makes its first appearance here, where our hero is tasked with an almost impossible challenge.

~

The old Western Zhou era script shows a compound character. The left side is the symbol for a path, the same as that shown in the Dao. The right hand side show a heart on the bottom. And on the top is a drawing that means “in the center.”

I translate it as:

the Dé—an Ethics system that’s the straight-heart-core of the way

~

Here, in its first appearance, we learn that the Dé is tied to the mysterious structure that underlies the deep union [and yet surface separation] of Being and Not-Being. And based on its appearance in this chapter, it’s all tied to our hero’s challenge. How?

How does the Dé help our hero combine all the complex tasks necessary for this dual role? In the next chapter, we get more details on how this matched pair and its figure-eight structure loop together. Until then, please use the contact form to send me your comments. I look forward to each one. And thank you for being here.

Seriously. It is. I imagine you can see where my physics-happy mind goes!

Seriously. It is. I imagine you can see where my physics-happy mind goes!