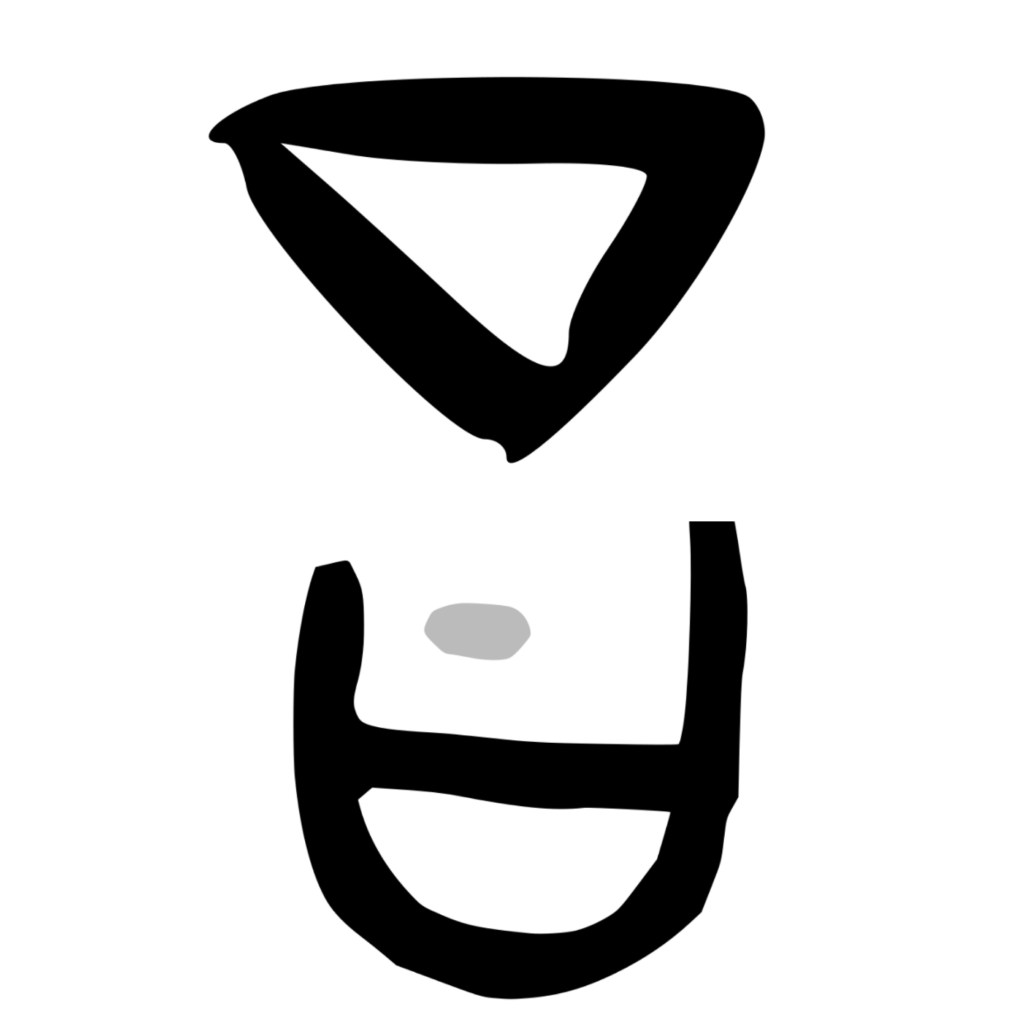

jiû (久)

Heaven (that sky level above the human head)…

lengthy as hair that has to be tied with a brooch;

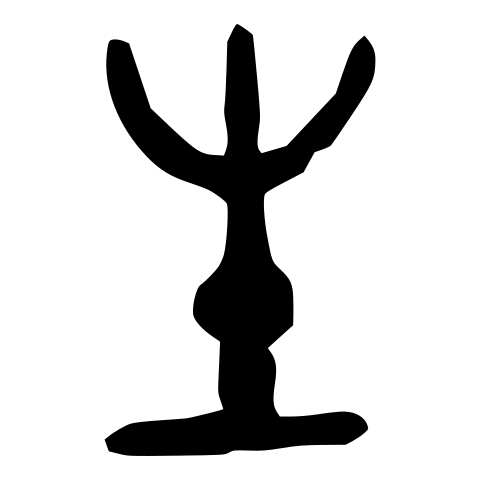

Earth (this soil vagina)…

enduring for years—like someone receiving moxibustion treatments with mugwort used for cramps, turning a breech baby, or other health issues;

Thus begins Chapter 6.

Lâozî’s referred to Heaven-Earth several times by now:

- In Chapter 1, we learned that Not-Being personal naming is Heaven-Earth’s beginning—like conception in a woman.

- In Chapter 5, we learned that Heaven-Earth is not really personable, and it has an interstice that is like a bellows.

- Last time, in Chapter 6, Lâozî said the double-winged gateway of the hard-to-see structure of a mother’s lap (vagina) is called Heaven-Earth root of the family tree (penis)… and is barely perceptible. Also: surviving.

Here, though, Lâozî’s pulled Heaven and Earth apart and is telling us something about each one, on its own. Heaven is long. Earth is enduring. Dào Dé Jīng translators variously say heaven is eternal or long-lasting and earth abides or is everlasting; or they lump them together and say they are enduring, or infinite and eternal.

In our last discussion of Heaven-Earth, I went into the images a little more, the history of each word, their association with all these pregnancy pictures… and confessed that I think Lâozî’s using a sort of double code where Heaven represents not only an abstract idea of a place/state but also a literal celestial spirit. Like: a person’s soul. And Earth represents not just this earthly plane but also an actual womb like the one pictured in the original glyph. That would mean that in the first line of Chapter 6, Lâozî’s just told us that a fetus is alive and also the womb is intact. Next we learn how that affects the combo of the two, when considered as a “place” or unit:

Heaven (that sky level above the human head)-Earth (this soil vagina)

‘place’— somewhere intentionally created, like a door chopped with an axe…

this means

capable—powerful as that legendary bear with deer legs—of

“lengthy as hair that has to be tied with a brooch…”

abiding for a long time—the erect penis of a male ancestor—

“enduring for years—like someone receiving moxibustion treatments with mugwort used for cramps, turning a breech baby, or other health issues—”

—now this is cooking!

Yes, now we’re cooking! The celestial spirit in the earthen womb can be long-lasting for a long time and endure like someone receiving moxibustion treatments with mugwort used for cramps, turning a breech baby, or other health issues. Moxibustion really was, and still is, used in Chinese medicine for the exact OB/GYN uses described here. The pictogram of that process evolved to the modern character 久 (jiǔ) meaning a long time, presumably because it promotes health and longevity. This is the first place this character occurs in the Dào Dé Jīng. And what does it mean for our story? The next lines say:

This means

what it holds a basket of…

the husk of the initial protective bud casing—the sepal—but not really the true inner flower of

of course—one’s self personally, right on one’s nose…

birthing—a bud sprouting from the ground;

anciently, for ten generations, this therefore lightly hits and leaves a mark of reason…

“capable—powerful as that legendary bear with deer legs—of

lengthy as hair that has to be tied with a brooch…”

birthing—a bud sprouting from the ground.

So: not really oneself birthing, therefore capable of long-lasting birthing.

Okay, even if you don’t agree, you must admit that you can see how I might imagine that our midwife someone from the last chapter has just prevented premature labor and thereby allowed our hero to be birthing later?!

And how in the world do other translators make sense of this line, you ask? Referring to Heaven and Earth, they say:

- Yi Wu: Is because they do not live for themselves. So, they can live long.

- Feng and English: They are unborn, so ever living.

- John C H Wu: Is it not because they do not live for themselves

That they can live so long? - Chao-Hsiu ChHen: because they have no ego; therefore they can live for ever.

It’s not that I disagree with these interpretations. It’s just that I wish we didn’t have to lose that other level of the earthy, intimate, domestic, human parts of life that Lâozî use to convey those lofty ideas.

And there’s more. As a result of all of the above, the sage’s life is a certain way:

The sun—walking across the sundial a while, stopping a while—sees indeed

this means…

the grounded sage—listening and speaking, standing connected to earth as well as the heavens,

that person:

being behind—what remains afterward when stepping slowly, only one’s left leg leading the way, leaving the tiniest of silk thread footprints—one’s descendants…

what it holds a basket of…

one’s pregnant self,

The sage’s pregnant self is behind… or it’s what’s left behind. It’s the sage’s descendants, you could say.

and yet now, bearded, you: (ér, 而)

one’s pregnant self…

being long before—like one’s dead ancestor;

So, at the same time, that “bearded” pregnant self is ahead… it’s the sage’s ancestor, you could say.

It’s a paradox that most translators describe as: the sage puts himself behind and therefore is ahead. The description of the sage continues:

‘outside’ or foreign—like the relatives of your mother, sister, and daughter who divine by the moon…

what it holds a basket of…

one’s pregnant self,

and yet now, bearded, you:

one’s pregnant self…

surviving—on the plane of a baby with health issues, maybe a large head, but still sprouting;

Once more, phew: surviving despite being foreign or an outsider (with suspiciously witchy female relatives, at that!). And here’s what happens as a result:

breaking the little wings off…

this means…

what it holds a basket of…

Nothing—no one dancing with long tails flowing from their wrists—nope never, no way, nowhere, nohow Not-Being (wú, 無)

personal concerns—like about one’s private grain field—

of a disastrous nature—like that disease-causing environment around Tusk Town—

This reads like a double or triple negative! I see it as: this stops the sage’s Not-Being from potentially disastrous personal concern. (Also it makes me wonder about Tusk Town! Some think it was the old name of Langya. What calamity happened there—was it swampy and malarial? Was there some kind of unwholesome behavior thereabouts? In Classical Chinese medicine the term referred to pathogenetic factors… were there a large number of children born with issues? I can find reference to sulfur springs in the area, so maybe it was just the smell?) Anyway, as a result of this…

therefore—anciently, for ten generations, this lightly hits and leaves this mark of reason…

capable—powerful as that legendary bear with deer legs—of

completing—that final nail in the weapon on a pole—

what it holds a basket of…

personal concerns—like about one’s private grain field

Now the sage can complete his personal concern.

Without my habit of seeing the character Not-Being as a persona, it gets even more complicated: “stopping not being unhealthily personally-concerned means the sage can complete his personal-concern?”

Here’s how others translate this passage:

- Yi Wu says: Is it not because he has no self that his self is realized?

- Feng and English: Through selfless action, he attains fulfillment.

- John C H Wu: Is it not because he is selfless that his self is realized?

- Chao-Hsiu ChHen: Only through unselfishness can he achieve fulfillment.

Much easier to read! And I’m not saying they’re wrong, of course. But I like seeing where Not-Being shows up, especially after all that pregnancy and moxibustion. And I like seeing where the “bearded, you” appears.

To me, in the sub-text story, the day has been saved—that labor from the last chapter has been averted by moxibustion performed by our midwife-someone. And that means that our pregnant sage adopts a beard and sallies forth into this new double life.

Ok, well we CAN agree that the sage gives up a certain kind of personal concern in order to complete another kind of personal concern. That seems to be true no matter whether you agree with my imagination or not! And now here we go… into Act 2 and a whole new world with this new kind of selfless self in action.