zhì

Last time we were looking at what the traditional version of breeding does to our old friend, fū, this particular grown man:

breeding—like a gentleman holding a fountain pen making something happen—

that is to say, this particular grown man with a hairpin and public courtesy name…

“firing arrows from the mouth—sure” as the sun, daily…

—now this is cooking!—

the husk of the initial protective bud casing—the sepal—but not really the true inner flower of

daring—lightly hitting ears on both sides of the head—

efforting—like lifting up an elephant…

—yes, that too, vagina!

efforting—like lifting up an elephant…

nothing—no one dancing with long tails flowing from their wrists—nope, never, no way, nowhere, nohow Not-Being

efforting—like lifting up an elephant;

We left off with that evocative “efforting… Not-Being efforting.” Here’s what comes next:

after following this sacrificial blade-and-cauldron-like ritual example, standard, or regulation…

nothing—no one dancing with long tails flowing from their wrists—nope, never, no way, nowhere, nohow Not-Being…

the husk of the initial protective bud casing—the sepal but not really the true inner flower of

“governing—regulating by harnessing the river named Happy or speaking of turning yourself.”

What we learn here is that in following that example of the grown man who doesn’t really dare efforting… efforting Not-Being efforting, then Not Being… not really governing.

Lâozî used this same “governing” character zhì (治) earlier in the chapter when telling us about how the sage governs. There we learned that because breeding civilians a certain way had a certain effect, “the sage has this governing” which Lâozî described in some detail for us.

~

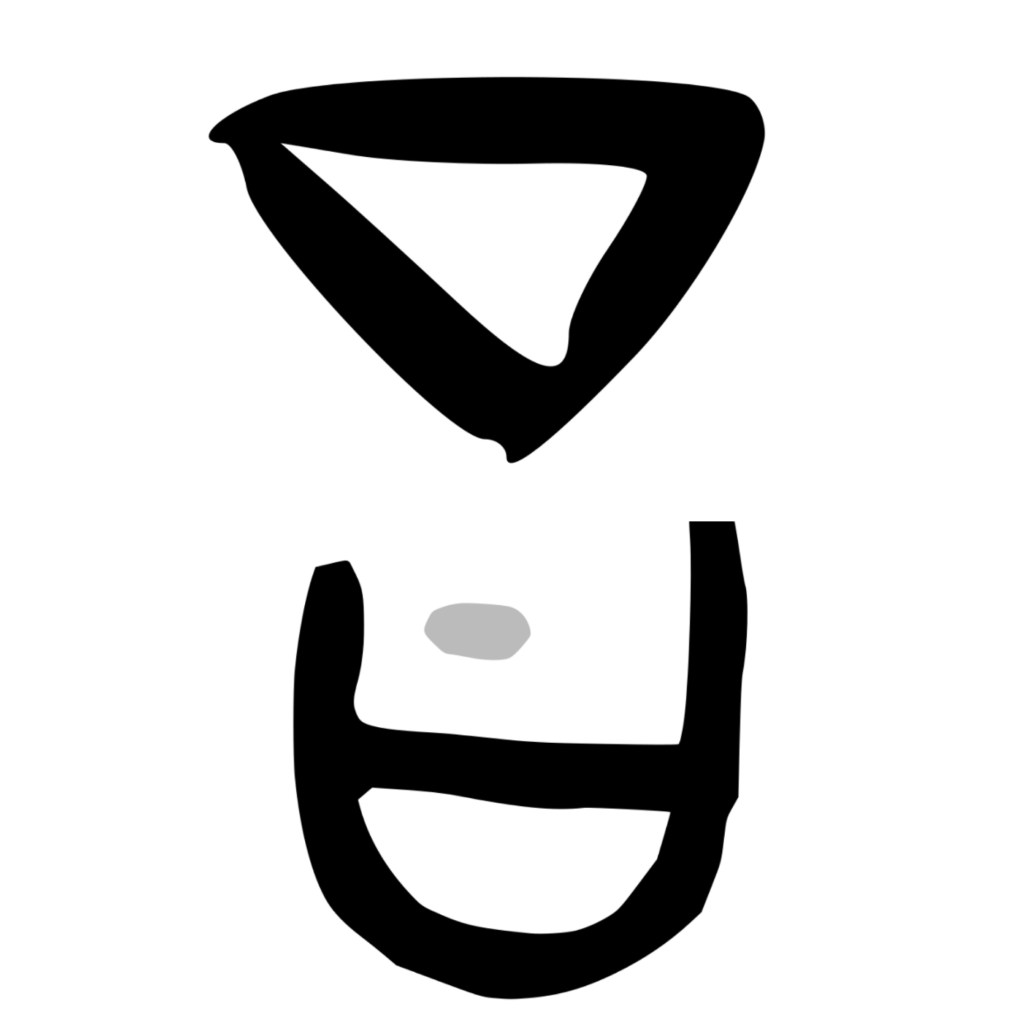

Remember, the zhì (治) character shows water or a river in its left sub-component. The right sub-component is a pictogram incorporating a mouth below a very mysterious element, 厶. I mentioned before that this element variously been identified as a plow turning, a fetus finishing in the womb, or an abstract symbol for being selfish, but I decided to look into it a little more today. Its bronze inscription glyph looked like this:

It’s such a classic and evocative symbol in all of the oldest cultures. What does it “mean?”

The oldest etymology of Chinese characters was compiled in the Shuowen Jiezi during the Han dynasty. From what I can tell, a lot of etymology still references this work, though more recent discoveries about the oldest oracle bone scripts seem to have really cast doubt on its conclusions. The Shuowen Jiezi’s description of this mysterious triangle said that “in olden times, when Cangjie invented the system of writing, a self-encircling element was designated as the character for ‘private.'” They compared it to the symbol for ‘public’ which was 公, and it is possible to see the connection when looking at the modern characters.

But this is a good example of how the Shuowen Jiezi’s descriptions were flawed since its author(s) didn’t have access to the oldest scripts. It turns out that the bronze inscription for the “public” character looked like this:

And the even older oracle bone script like this:

You can see there’s no triangle. But by the time of Shuowen Jiezi, the 厶 character had evolved to look like this:

Now you can see how the Shuowen Jiezi authors thought it was related to the character yî (以) which we investigated in a previous post. I translated it as already… finishing it in the womb based on its typical translations and the original pictogram which is said to be either a snake or a fetus as it came from this bronze inscription:

And this original oracle bone script:

But neither of those resemble the triangle that was the original symbol for the 厶 we see in our character zhì (治). We still don’t know what the triangle symbol originally meant, though I think we are safe in saying it’s not necessarily the opposite of “public.”

We might learn more about the triangle by looking at how it was combined with the pictogram of grain to make the character sī (私), which some people believe meant a person’s private grain field. It now means self, private, personal. In Classical Chinese it meant I, me. In later times it morphed into not only self but even selfish as well as illegal, secret, stealthy. Most recently it’s the word that means to Private Message or Direct Message someone on the internet!

I’m going into this detail not only because I find it interesting but so you and I can remember how tricky it is to go with the modern or even sort-of-old meanings for the old glyphs of Lâozî’s time. If you’ve been following along, you’ll note that my previous posts and definitions of terms were more influenced by newer meanings that they are now. The more time I spend with the glyphs, the more I don’t trust the modern definitions or even the Shuowen Jiezi. So I will now be going back and changing any translations where I used the “selfish” or “private” connotations for these characters discussed here.

MEANWHILE what does the triangle mean?!

Let’s look at the whole right sub-component of zhì (治). Here the triangle character (厶) sits atop a mouth. Here’s what those original glyphs might have looked like together:

This was the original character for the word happy but then evolved into talking about oneself or I/me. (When that happened, the character for happy became 怡. You can see that they just put a picture of a person in front of the original character. This is such an interesting and typical kind of evolution in the language.)

Combined with its left hand component which was the picture of a river, a glyph version of zhì (治) would have looked like this:

I think it’s still difficult to say what the triangle alone meant, but putting the pieces altogether, here’s my translation of zhì:

governing—regulating by harnessing the river named Happy or speaking of turning yourself—

*I love this image as a representation of governing. It revolves around one’s self in the best way: Harness the River Happy! Turn yourself somehow and speak of that! No wonder Lâozî used this character to describe a sage’s governing. My favorite leaders have in fact acted in just this way. How can I implement this in my life? How can you?*

~

Back to the end of Chapter 3 where we saw Not-Being… not really truly governing like the sage.

If Not-Being were the negative particle “not,” then we’d have a double negative here: not not-really governing. That would mean that after following the example described in the previous post, there is this kind of governing happening. That feels so dang convoluted. But maybe Lâozî does indeed use all the “nots” to emphasize that all this is such a receptive and non-grinding way of going about things.

On the other hand… what if Not-Being is actually a person with non-person status—a non-being? Then the text would mean: after following this example, the Not-Being isn’t really governing.

What’s the correct interpretation? Well there’s no way to know of course. Each translator and each tradition has its own idea. It’s tempting to simplify things so I can land on an answer, but I try to withhold making conclusions until I’ve read the whole Dào. And… we have quite a long way to go! I know it’s frustrating, but for me that’s balanced by the thought experiments, take-aways, curious puzzles, and tiny hints we find in each character, line, section, and chapter. I hope you’re finding some satisfaction too, as well as some of that disorientation that must be part of Lâozî’s plan.

Next time, I’ll prepare a summary of Chapter 3 that hopefully will clarify things without getting rigid. Until then, please use the contact form to let me know your feedback. I love the comments I get, and if you haven’t sent one yet, now is a good time to start. Thank you for that and for being here.