shēng

Birthing (生, shēng) sounds familiar to you because in the first half of Chapter 2 this word linked Being and Not-Being in a list of “opposites.” Lâozî told us that Being and Not-Being are mutually birthing.

~

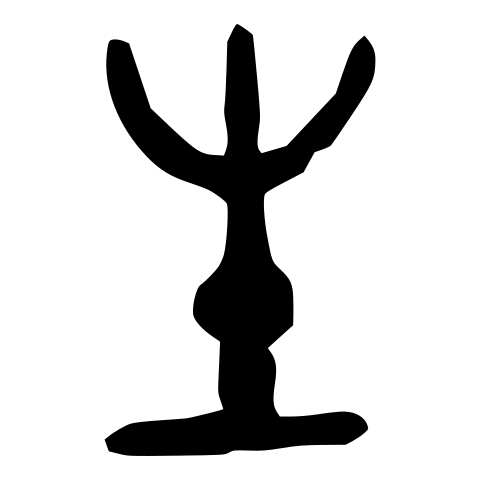

In Western Zhou Bronze inscription script, familiar to and possibly most similar to the script used in Lâozî’s time, shēng looks like this:

This image is a compound of a sprouting new plant:

And the ground:

I especially like the added bulge. To me, it really augments the meaning of this character because the modern translations of shēng are to live, subsist, exist; grow, develop, bud; bear, give birth, bring up, rear; and be born, come into existence. It also can be a noun: offspring, descendant; disciple, student; Confucian scholar; or life, existence, being, living. And it can be an adjective/adverb like fresh, not stale; unripe; raw, uncooked; uncultured, uncivilized; strange, unfamiliar; vivid, strong; innate, and natural. In Buddhism, it can mean to go into society or be reincarnated.

Here are some of the different ways translators of the Dào, in particular, interpret shēng: arise, creating, give birth, rears, produces, and lives. And that’s just in this chapter. Elsewhere you find those same translations as well as be born, and foster. Most translators use more than one definition, many use more than one even within this chapter. You can see why—the possible meanings vary so significantly in nuance. Is the thing in question being birthed or giving birth or raising something up? Those are all very different, and it’s tempting to want to clarify.

Because this word is so often interpreted as birthing, I originally had a baby in my definition, but as I wrote this post, I realized that’s an addition on my part. The image only shows the plant, the ground, and that added bulge (which does put me in mind of a baby, but it could also be a meristem from which new leaves are going to grow). My translation is hereby corrected to:

birthing—a bud sprouting from the ground

I like it because it has that poetic multi-usefulness. It could refer to doing the birthing, being birthed, growing, or even being raised.

~

In the first part of Chapter 2, we learned that Being (yôu) and Not-Being (wú) are mutually birthing—a bud sprouting from the ground. Based on the lesson in the previous few lines of that chapter, this first seemed to me to mean that if you work hard to “effort” Being, then you’ll cut off and define Not-Being while it’s still developing on its own.

And vice versa? Possibly. Though it’s not definitely clarified for us, that word “mutually” could be seen to imply that. Maybe it even means that you can’t have Being without Not-Being and vice versa. That’s a very common interpretation of this lesson and goes with the pictogram for “mutually” (xiāng, 相) which shows a seen tree and the eye seeing it.

Maybe Being and Not-Being are two aspects of one phenomenon—maybe Not-Being is the life force that makes sprouts sprout, and Being is the actual physical sprout? Or maybe one is the ground and the other the sprout? Maybe their union creates life. I like that one.

One thing is for sure, we are definitely wandering once more in the uncertainty of the Being-Not-Being mystery. Again I wonder…

What exactly are these Not-Being and Being characters, anyway?!

- As we’ve seen, they are often used as negative- and positive-particles.

- But also as adjectives.

- And in some places—like the previous paragraph—they’re standing on their own.

There are other negative particles in the Chinese languages—ways to negate a concept, i.e., to say “not__.” And other ways to say something positively IS happening. These two characters were decidedly not the common way to do either in Lâozî’s time.

Using these very human-tinged characters in so many different ways gives the characters their own sense of being actual characters. And always with a twist. Every time Lâozî uses them, it’s sort of a pun… a double entendre.

- Are they actually separate people?

- Are they two sides of every person, situation, and thing?

Thus far, it remains shockingly, beautifully unclear.

Further down in the chapter, we started to learn about the ideal grounded sage and were told that when it comes to “staying,” the sage’s personal role was Not-Being efforting. What does that mean?

- Of course this could just mean the sage “remains not forceful.” That’s the most common interpretation, and a lovely and useful one at that.

- But given the lesson in the lines immediately preceding these, I assume it also is telling us that when it comes to “staying,” the Not-Being aspect of the sage is efforting—trying hard.

- And that when the sage’s Not-Being aspect tries to force something—to “effort”—the sage shifts from the shamanic, dancing Not-Being mode into a more concrete, outer-oriented Being. The sage has both aspects.

- Or maybe the sage is that dancer—that Not-Being—and when it comes to “staying,” well… that is the sage making an effort.

Now even later in the same chapter, we’re told that when it comes to “birthing—a bud sprouting from the ground,” the sage is just the husk of but not really the true inner flower of Being, i.e., bù-Being. This other negative particle, bù, is a pictogram of a flower’s sepal or guard petals and in every way a completely different character than Not-Being’s image of a mysterious dancer. So this new information isn’t saying that when it comes to birthing, the sage is definitely in some sort of Not-Being role. It just says that when it comes to birthing, the sage isn’t really Being, even if it may look like it initially.

~

It sounds confusing, doesn’t it! It helps me to diagram it like a flow chart. To summarize what we’ve learned in Chapter 2 about birthing/sprouting and our favorite characters: Being, Not-Being, and the sage.

- Being and Not-Being are the type of duo with a mutual relationship wherein defining one means you define the other by default. In their case, they are in fact mutually birthing/sprouting.

- When it comes to staying, the sage‘s personal role is Not-Being efforting.

- When it comes to birthing/sprouting, the sage is just the husk of but not really Being.

Every which way I re-arrange and re-phrase that to myself, it does seem the sage’s more identified with the Not-Being aspect.

It’s a lovely message in keeping with what most people make of the Dào: the wise person has a certain hard-to-describe, beautiful, mysterious, intuitive, flexible, unattached way commonly associated with mystics from the Buddha and Jesus to Rabia, Rumi, and Hafiz.

It’s interesting to consider what it might mean in our own lives to de-emphasize Being and feel our way into more Not-Being. It’s a hard thing to describe, but it feels spacious and restful and energizing. Experimenting with this sensation in the odd moment here and there—that’s my wish for you. And please, write to me with any feedback, questions, ideas that come from those moments. I love hearing people’s experiences with this concept.

~

Meanwhile… if this is one of the points of the text, why does Lâozî say it so obscurely? Is Lâozî making it intentionally hard so that by the time the reader finally figures it out, it’s fully integrated? Or maybe so it can mean many different things and therefore be useful to many different people in many different circumstances? Is it because this is the way to make words go together to fit a rhyme, alliteration, and meter scheme? I do think all of these are reasons the text has captivated people for millenia.

Or is it because the concept of Not-Being as the sage’s true creative essence was so hard to accept that it needed some disguising? We’ve seen that Lâozî does, after all, draw characters that are masked, hidden in caves, bearded, a husk and not the real thing, or a hard-to-see mystery within a hard-to-see mystery. Next time we’ll summarize Chapter 2 the way we did Chapter 1, and maybe more ideas—or questions—about this story will come into focus.

Thank you for joining me once again! As always, please use the Contact form to write to me until then—I really look forward to hearing from you.