cún (存)

We left off pondering the exact nature of what appears to be a call to The Way of the loose-haired chieftain. (I apologize for the week off. I hit a big milestone in completing the screenplay treatment for a film version of Lâozî’s journey!! More on this later, as you might expect, but for now we return to how I pieced all this together.)

Happily, in the next paragraph of Chapter 4, Lâozî tells us more about this phenomenon of how you can be pouring water from a hollow drum and yet now, bearded, doing water-bucket-style work but not really overflowing one’s vessel:

In all four directions,

the myriad scorpion medicine-dancing Ten Thousand

Things cut off from you—all external matter like cows etc.—

has this

ancestral shrine:

So first we learn that everyone everywhere has honored what The Way calls one to do.

And then we get more information more about what this “ancestral shrine” involves:

pushing down to a sitting position on the ground…

what it holds a basket of (qí 其):

a person speaking like an axe on metal—sharpening;

removing—a blade cutting the horn from an ox…

what it holds a basket of:

unravelling—separating thin silk with a blade into disorderliness;

harmonizing as a mouth organ…

what it holds a basket of:

brilliance—that shining fire over the head of a kneeling person;

Remember our discussion about “what it holds a basket of?” We were trying to figure out where this character points—in other words, what is the IT referred to? I concluded that this phrase doesn’t necessarily refer back to the word right in front of it. It most often points the reader back to the most recent “subject.” That would be this ancestral shrine (i.e., the call to The Way, to be pouring water from a hollow drum and yet now, bearded, you’re doing water-bucket-style work but not really overflowing one’s vessel).

Indeed the very careful and respectful translator, Yi Wu, translates this section to say The Way… blunts its own sharpness, unties its own tangles, tempers its own brightness.

BUT then again, in many places, many translators say “what it holds a basket of” DOES refer to the word right in front of it. In that case, you’d interpret this passage to mean that when it comes to The Way: pushing down to a sitting position has a sharpening similar to that of a person speaking like as a metal axe; removing like a blade cutting the horn from an ox has an unravelling like separating silk thin with a blade into disorderliness; and harmonizing as a mouth organ has a brilliance like that of shining fire over the head of a kneeling person.

As usual, it works both ways, in that manner typical of great poets and Lâozî in particular, adding up to all the paradox and ambiguity one might want in a mystical text!

Whichever “it” you consider…

spoken of altogether with one another—like all earthly, mortal, commonplace plates…

what it holds a basket of:

leaving dusty footprints in the dirt—like a deer streaked with soil.

We’ve seen this kind of naming in which things are “spoken of altogether” before. In the very first chapter, Lâozî described how Being and Not-Being are a matched pair that’s spoken of altogether when stepping out of their cave… at which point they then acquire differently-masked names. Now, presumably what’s being spoken of altogether is The Way… of pouring water from a hollow drum and yet now, bearded, you’re doing water-bucket-style work but not really overflowing one’s vessel. And this phenomenon leaves barely discernible tracks.

AND/OR: speaking of things altogether may, itself, have the characteristic of leaving barely discernible tracks.

Furthermore, it’s even harder to see whatever-this-is because it’s:

Concealed like sugar cane sweetness tucked in the ends of folded cloth and frozen like ice…

—Oh! A breath, like wind through tree branches!—

But also:

bearing a side-by-side personal resemblance, seems like:

“this particular territory—this enclave, defended by a weapon on a pole, plus its surroundings…”

surviving—on the plane of a baby that has health issues, like maybe a large head, but is sprouting. (cún, 存)

If you look back up to the top of this post, you see this particular territory—this enclave, defended by a weapon on a pole, plus its surroundings... was used in the first line of this Chapter 4, in what I’m considering to be The Call to Adventure. And now here we learn that the “territory” of this calling (to be pouring water from a hollow drum and yet now, bearded, doing water-bucket-style work but not really overflowing one’s vessel) looks very much like when an ill newborn survives and grows.

~

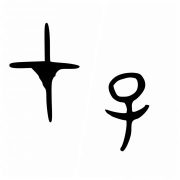

Let’s look at the character cún (存). It’s a compound character made from these two bronze inscription glyphs:

The sub-component on the left (cái, 才) is a pictogram of the sprouting of seeds. On its own, the modern meanings are ability, gifts, talent, or a person’s status/background. In Mín Nan (remember the Mín people?), it’s used as a classifier for describing a volume of wood or area of paper or other sheet materials. It’s considered the phonetic element of this word, signaling to the reader to give it that “c” sound. My first translation kind of ignored this character, but I’ve added it is to be consistent with my goal to represent all images found in the glyphs. Doing so with this character is especially satisfying to me as in my other interest—physics—surface area is one of the master keys to understanding most phenomena. And since we see references to marking out 2-and3-D spaces elsewhere in the text, it helps tie together potential connections to be consistent and include it here.

The sub-component on the right (zî, 子) is considered the semantic part that gives the character its meaning. The pictogram is an image of a baby. Etymological dictionaries specifically say it’s “a baby with a large head and spread arms; the legs are wrapped in a blanket.” Its modern meaning is child, offspring, son, and descendant. But also it can mean master or teacher, and indeed was used as a suffix in Lâozî’s own name as well as Confucius’ name (Kôngzî). It’s also used as the alternate for seed and can mean egg, young, tender, or small.

The overall compound character translates as exist; cherish, harbor; store, retain; stock, reserve. Dào translators use different words in different chapters, ranging from exist, be present, and is there, to preserve, survive, and places where it’s hard to even figure out what they’re actually calling this word because it’s combined with the other words around it into a new phrase.

I can’t help but believe it’s a mistake to ignore the character’s original image so thoroughly. Because I believe that Lâozî’s given us a detailed picture of The Call: its revered nature, what it does, and what it looks like. We don’t want to discard any information in that message even if it would simplify things to do so! The description we end up with is mysterious and provocative as usual.

Consider there’s that bearding… and it leads directly to a result that resembles a newborn baby living through health issues. Maybe it’s because of that last line that so many other images in the chapter bring pregnancy, childbirth, and gestation issues to my mind (e.g., pouring water from the center like from a hollow drum water, pushing down to sitting position, and even removing something that’s unraveling).

But also the more typical interpretation of this chapter’s meaning is compelling. Consider Yi Wu’s translation:

“The Way appears empty;

in use, it may not overflow.

Fathomless, it seems to be the ancestor of all things.

It blunts its own sharpness,

unties its own tangles,

tempers its own brightness,

unites itself with dust.

Deep but clear, it seems to exist and not to exist.”

And that of Gia-fu Feng and Jane English:

“The Tao is an empty vessel; it is used, but never filled.

Oh, unfathomable source of ten thousand things!

Blunt the sharpness,

Untangle the knot,

Soften the glare,

Merge with dust.

Oh, hidden deep but ever present!“

It’s one of my favorite passages. That may be partly because it’s the first one I ever considered closely. When I met my husband and discovered his copy of Feng and English’s translation, I found a piece of rice paper tucked inside onto which he’d copied these very lines.

Why those lines, I wondered? How does this shape his way of going about life? In fact, the more I’ve gotten to know him, the more I see how those lines describe him and his intentions so perfectly.

What do they feel like to you? Do they sound desirable? Boring? Attainable? Easy? Impossible? And… how would one go about living this way?

Now, too, the more I’ve gotten to know the Dào, I appreciate the Feng-English version’s poetry and simplicity, and yet when I read it, I miss seeing the glyphs’ images. I miss those references to concrete, daily life. I like to think that maybe those images not only serve as metaphors to get across the big abstract message that these other translators capture so beautifully, but ALSO describe some details of Lâozî’s world. What a masterful feat the sage accomplished if that’s so. AND it’s done with rhyme, alliteration, and meter! I hope you’re seeing more and more why I’m so fascinated with not just the text by its brilliant writer.

There’s one final line in this chapter, and we’ll look at it in the next post. Thanks for being here today. Please send me your comments and questions using the contact form. See you next time.