Here’s how I see it. Please consider it a light fanciful daydream if it offends your sense of the Dào Dé Jīng!

Setting the stage: conflict!

Yinxi the border guard recognizes Lâozî as he’s departing the country, allegedly fed up with politics in Zhou. He asks the renowned wiseman to leave behind some helpful words, presumably about his philosophy and the way to go about things. Lâozî says… well you might want to click here to read Chapter 1 and then pop right back. But basically Lâozî says…

The Way that I can describe to you as definitively The Way breaks the little wings off our traditional version of The Way.

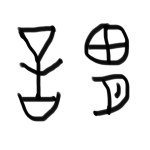

Wow. What a great first sentence. It’s very overt and rather patronizingly graphic in setting up all sorts of conflict and questions… especially with those actual Western Zhou Bronze Inscription characters that Lâozî used! (Yes, I’m making lots of assumptions here, as do all translators. Mine are described here.)

What follows sets up some idiosyncratic themes for the whole book.

Hair

Somehow hairstyle figures prominently in this first sentence and the entire text! Here’s my full version of the first sentence:

The Way of the loose-haired chieftain—walking a while, stopping a while, listening, and speaking of it all—about which you can purse your lips like a piece of cane and puff: “Yup, that’s it, definitely The Way of the loose-haired chieftain—walking a while, stopping a while, listening, and speaking of it all—” is breaking the little wings off the ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—or what we know as the timeless, whole-cloth ‘jin’ version of The Way of the loose-haired chieftain—walking a while, stopping a while, listening, and speaking of it all.

So we have a roaming prophet-like chieftain with loose hair. And then we have a sort of opposite: the current tradition in which men wrap their hair in a top knot on their head and cover it with a cloth as part of their puberty ritual. We’ll encounter some other hair and headdress images later in the book, but that theme’s established right here in the initial line.

What’s in a name

Different types of names also figure prominently throughout this whole first chapter. I count four different namings.

1.Above we learned about how when boys turned to men in ancient China, they received a new formal name.

2. The next sentence talks about the childhood name the boys gave up, a name you can still use with intimates after you’re a grownup:

Its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself urself by moonlight—about which you can purse your lips like a piece of cane and puff: “Yup, that’s it, definitely personal, childhood naming—what you say to identify yourself by moonlight” is breaking the little wings off our traditional its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself urself by moonlight.

[Yes, I shortened the ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—or what we know as the timeless, whole-cloth ‘jin’ version of (chàng) into “our traditional.” Yes, it’s both a big assumption on my part AND a useful space saver! That character’s described in detail here.]

So here’s yet another harsh difference between tradition and what Lâozi could say. This time it’s over personal naming in particular. Now we feel like names might be key in the conflict that’s been staged for us.

Lâozi goes on to differentiate two kinds of personal names: Being, its personal name, and Not-Being, its personal name. In this simple step, Lâozi introduces two of our most central and most baffling characters and puts them squarely into this naming conflict… but more on them later. Let’s see what other kinds of naming are discussed in the first chapter.

3. There’s also how things are spoken of altogether with one another—like all earthly, mortal, commonplace plates. Lâozi uses THAT title when talking about Being and Not-Being when they’re a yoked pair, just before they’re stepping out “of a cave” and into their two different, masked personal namings.

4. To really describe them altogether like that, Lâozi adds in yet another kind of naming: what it’s called when speaking from the gut—words, like slaves or criminals branded by a chisel emerging from a mouth.

Later in the book, we’ll see some significant permutations of these naming types, and we’ll really notice them too, since the basics are pointedly noted in the first chapter.

Being, Not-Being, their altogetherness, their differently masked names once they step out of the cave and get bearded, plus the crux of the mystery:

Most importantly, in this introductory chapter we meet and learn a little something about two of the book’s fundamental characters. The facts we get, in order of appearance:

- Not-Being is shown by a pictogram of a mysterious, shaman-like dancer and is often taken to mean “null” or “nothingness.” Lâozi tell us its personal naming is the conception of Heaven-Earth (merged to be something like… the whole universe or “heaven and earth”).

- Being is shown by a pictogram of a hand holding a piece of meat. Lâozi says its personal naming is the rearing, raising, or “suckling” of all the gazillion of material things in that universe, literally 10,000 Things—all matter external or cut off from you.

- In the traditional version, Not-Being is “wanting.” It’s missing something that’s been eroded, and that is a mysterious feminine essence called miào.

- In the traditional tradition, Being is “wanting.” It’s missing something that’s been eroded, and that is delineated surface—like a patrolled frontier border lightly hit with a sword tip from left to right (jiâo).

- Whoa, though! Really they’re a matched pair and can be spoken of in this state where they’re altogether—as common as daily dishes—stepping out of their cave…

- But. Once they step out, lots of “buts” apply. The first, main, and most unusual and specific “but” is a character that’s a pictogram of a beard (èr). The instant they step out, Lâozi starts describing them with a qualifier: and yet now, bearded…. Every time this èr character’s used, I can’t help but harken back to its intro here as a description of Not-Being and Being as they step out of the cave.

- So they’re altogether stepping out of a cave and yet now, bearded…. they have differently masked personal names (presumably this refers back to the “Being” and “Not-Being” personal names described before).

- What they’re called from the gut when they’re altogether has this hard-to-see darkness—the figure-eight structure of a skein of string-dyed-black (xuán). Based on how the text’s written, I think the entire set-up described beforehand—what I summarized in the above bullet points—constitutes that xuán. But I guess it could be something as yet unspecified, something that we discover later.

- And here’s the kicker… that hidden structure has its own hard-to-see dark figure-eight structure of string-dyed-black.

- And THIS, my friends, is the mysterious feminine essence’s double-winged gateway. Ending the first chapter here leaves us with miào feeling somehow central to the whole story.

What’s this have to do with our original conflict between The Way and our tradition?

I guess that’s the question Lâozî’s setting up for the suspenseful tale about to unfold to Yinxi, me, and you.

What stands out to you?

I’m going to give you some time to ponder this introduction and my question and send me your answers before I prejudice you with mine—because they’re doozies! And with that cliff-hanger… I thank you for being here with me and for sending me your comments. It means the world to me.