Dào

The first character in the first line of the first chapter of the Dào Dé Jīng (AKA Tao Te Ching) is, quite fittingly, Dào itself. I can think of no better way to kick off this new year and new decade than by starting here, at what is perhaps, after all, the end game of its author, Lâozî (AKA Lao Tze or Lao Tzu).

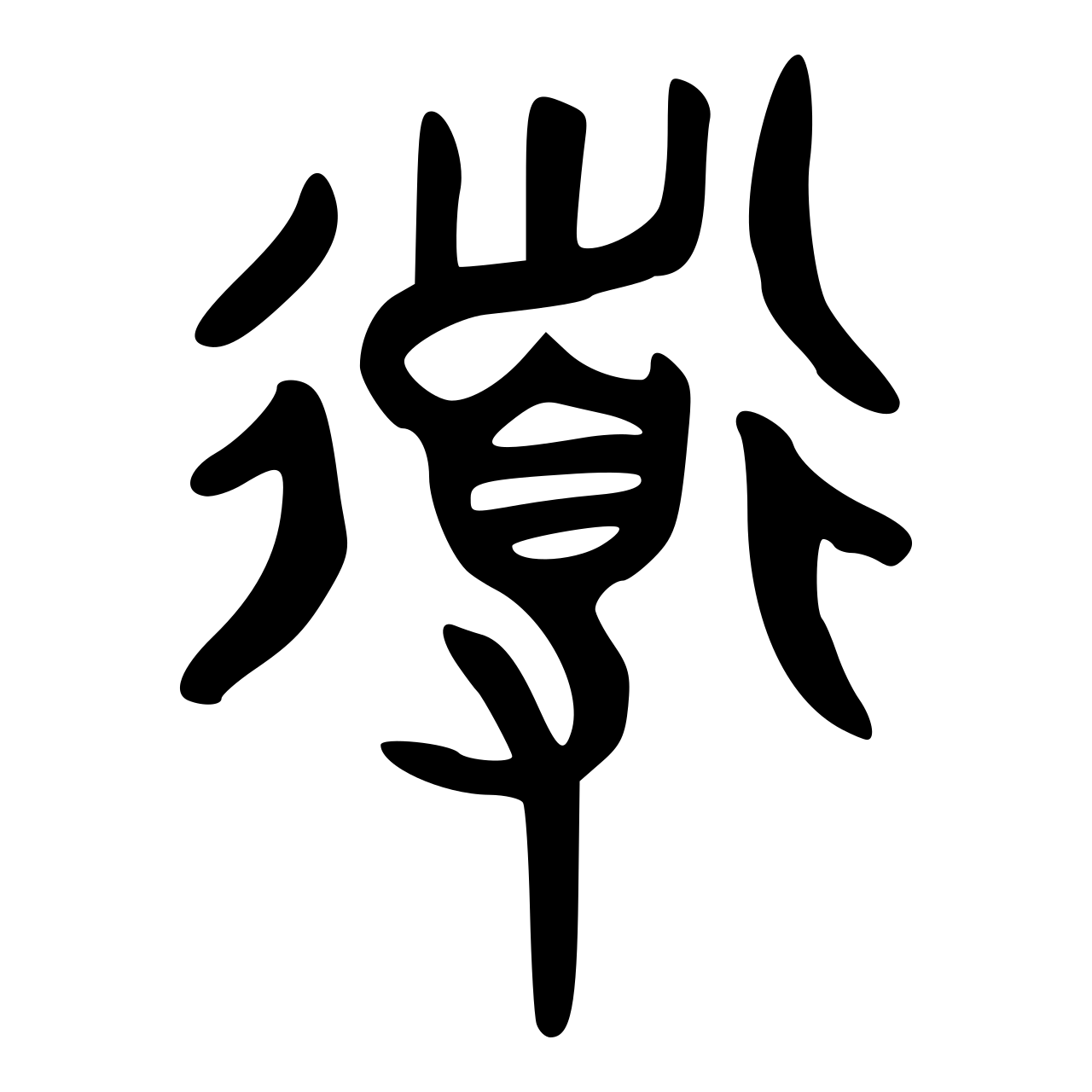

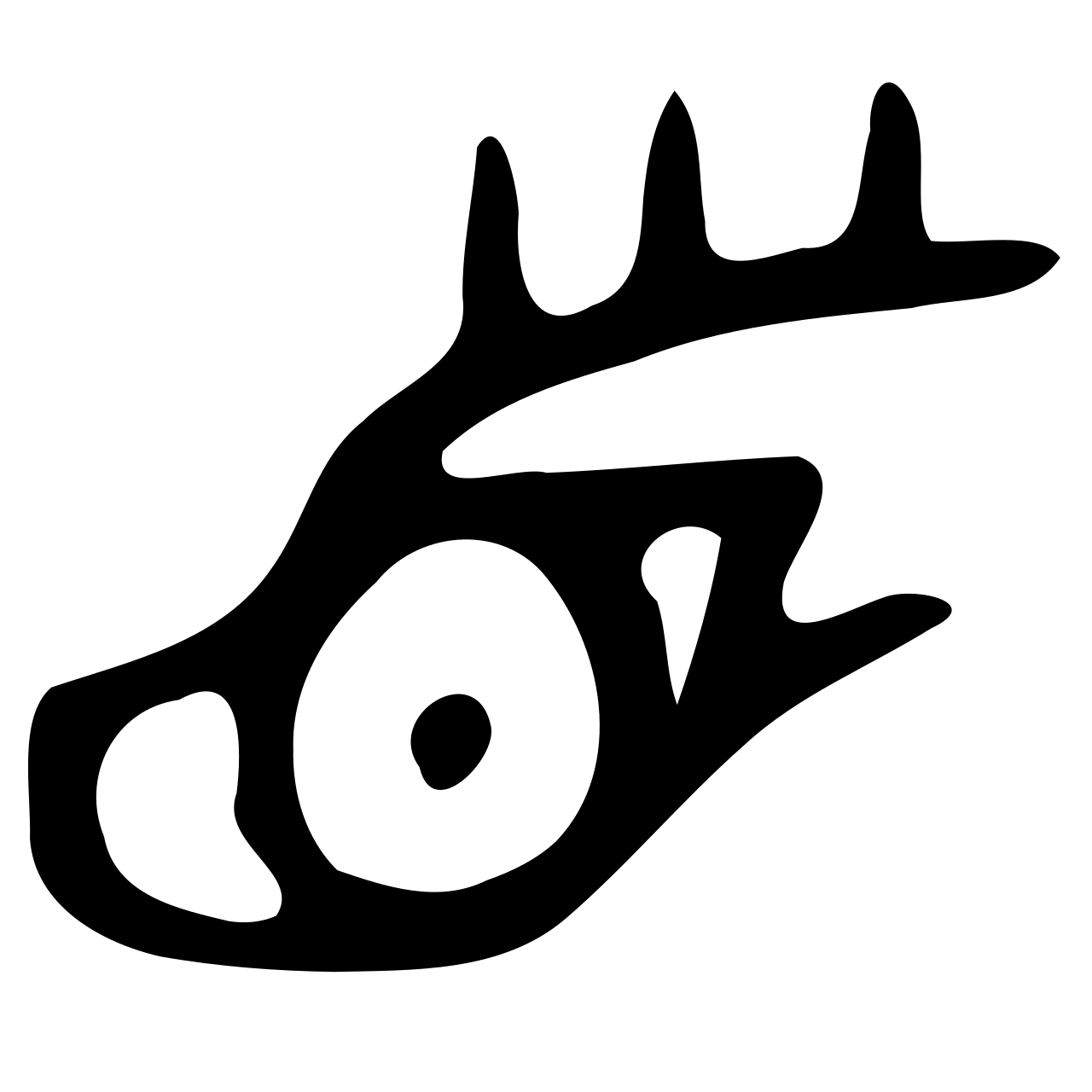

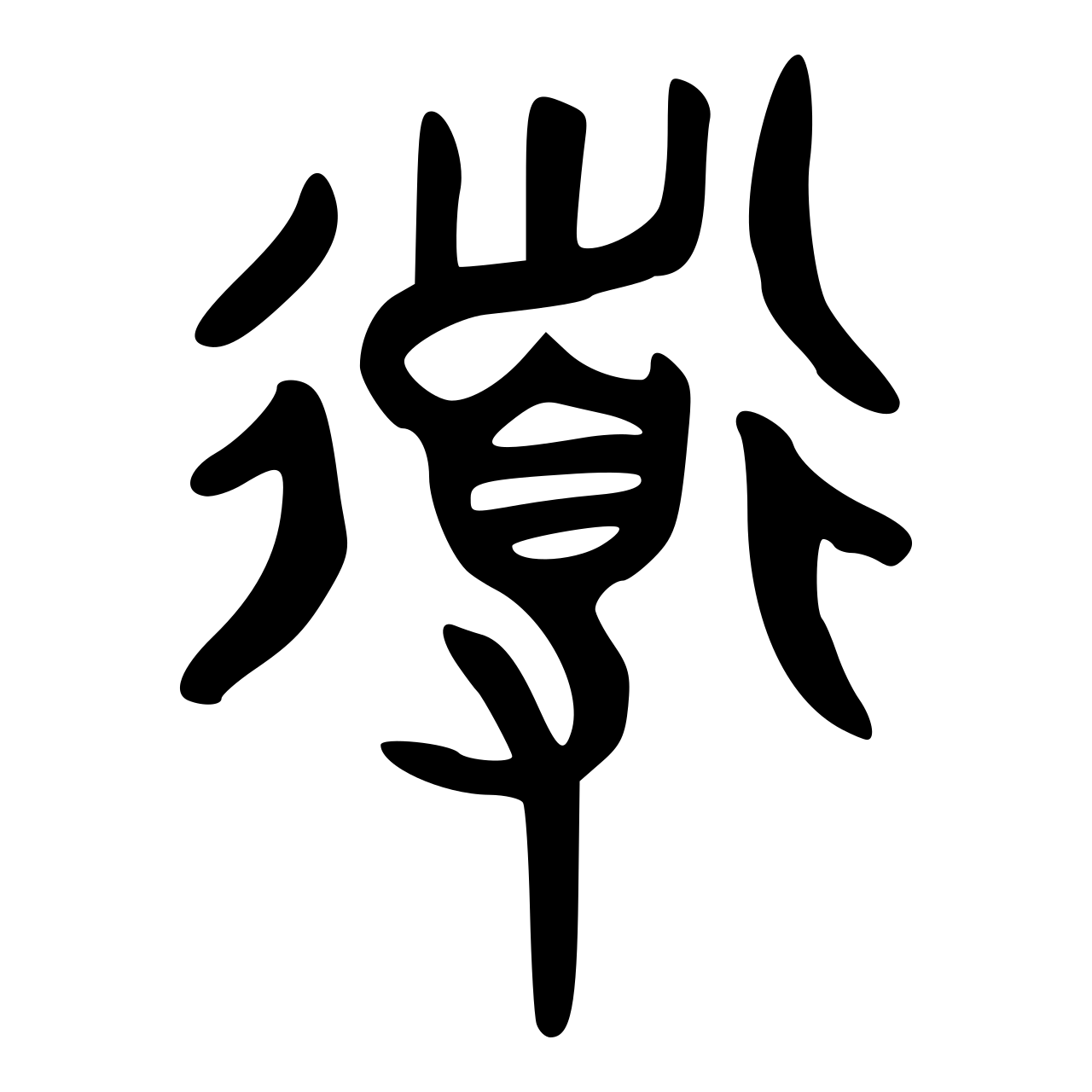

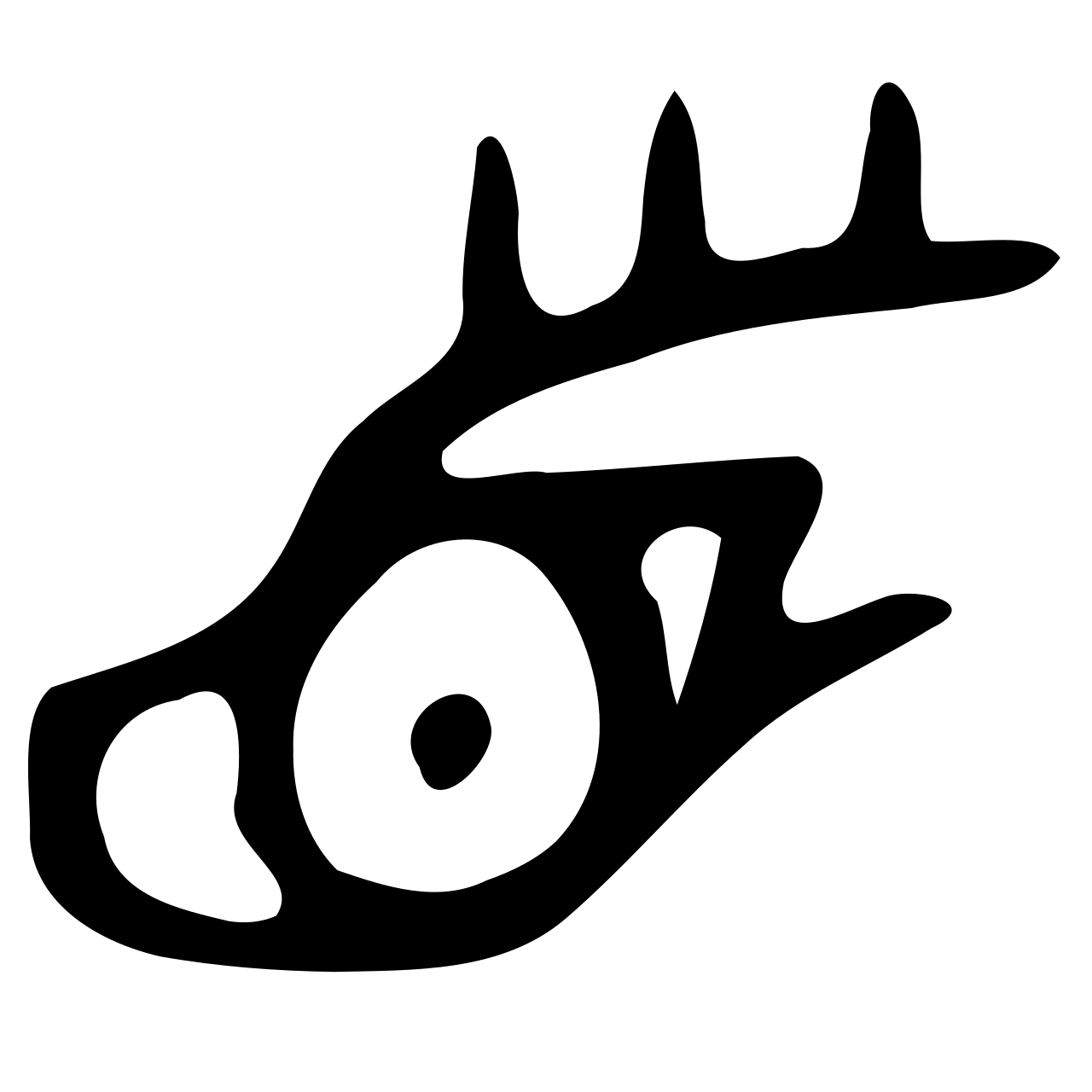

It seems likely that Lâozî actually wrote in something most closely resembling ancient Western Zhou Bronze Inscription script. Its glyph of Dào is shown above. The center part of the drawing shows a person with a long mouth and a pronounced head of hair. On its own, this sub-component means head or chief/leader and was drawn like this:

The marks on the outsides of the glyph mean step, and those at the bottom show a footprint, meaning to halt. In modern Mandarin script, these have been consolidated into one sub-component on the left side:

道

This character can mean explain; talk about; method or principle; and, more commonly nowadays, way, path, road. It has been translated as head in motion, walkie-talkie, or, more expansively, as traveling through life with one’s attention on non-duality or unity with nature. In Buddhism, it’s commonly called The Way.

So well known is this word that many translations simply stick with the Mandarin Pinyin transcription: Dào. In keeping with my goal of providing a translation that includes every pictorial element as well as the more abstract evolutions of a character, I translate Dào as:

The Way of the loose-haired chieftain—walking a while, stopping a while, seeing and speaking of it all

I have to come love this phrase and the person it describes—that person that I’ve come to think of as the author Lâozî. With each additional image, line, and chapter in this book, I feel we get closer to this wandering, free observer of life.

~

Chapter 1 of the Dào Dé Jīng introduces many key characters that appear over and over in the rest of the book. Each one is filled with the same kinds of subtleties you’ve seen in considering just this first word, so I’ll look into more specific words during the course of this week. But since this first chapter feels like a summary of The Dào and things to come, I present the entire first chapter for you below. As always, I give each character its own line, and each line from the original text is presented here as one paragraph.

~

1.

The Way of the loose-haired chieftain—walking a while, stopping a while, listening, and speaking of it all—

about which you can purse your lips like a piece of cane and puff: ‘Yup, that’s it, definitely

The Way of the loose-haired chieftain—walking a while, stopping a while, listening, and speaking of it all—’

is breaking the little wings off

the ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—or what we know as the timeless, whole-cloth ‘jin’ version of

The Way of the loose-haired chieftain—walking a while, stopping a while, listening, and speaking of it all.

Its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself by moonlight—

about which you can purse your lips like a piece of cane and puff: ‘Yup, that’s it, definitely

its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself by moonlight—’

is breaking the little wings off

the ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—what we know as the timeless, whole-cloth ‘jin’ version of

its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself by moonlight.

No-one-noway-no-never-nothing-nowhere-nohow-not-Being…

its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself by moonlight…

Sky(that level above the human head)-Earth(this soil vagina)

has this

conception.

Flesh-and-blood meat-holding-Being…

its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself by moonlight…

the swarm of Ten-Thousand Things,

all external matter—like cows—cut off from you

has this

suckling.

Anciently, for ten generations, this therefore lightly hits and leaves a mark of reason:

the ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—what we know as the timeless, whole-cloth ‘jin’ version of

No-one-noway-no-never-nothing-nowhere-nohow-not-Being…

desiring what’s wanting—what’s been eroded from this ravine…

this means:

keeping watch from the temple tower for

what it holds a basket of…

mysterious feminine essence—a few drops of that womanly mist;

the ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—what we know as the timeless, whole-cloth ‘jin’ version of

Flesh-and-blood meat-holding-Being…

desiring what’s wanting—what’s been eroded from this ravine…

this means:

keeping watch from the temple tower for

what it holds a basket of…

delineated surface—a patrolled frontier border lightly hit with a sword tip from left to right.

This here—the foot stops a person here on their footprint:

a matched pair, like a harness of ox yokes

—now this is cooking!—

altogether with one another—as together as a commonplace plate with a mouth—

stepping out of their cave,

and yet now, bearded:

differently-masked,

its personal, childhood name—what it says to identify itself by moonlight.

Altogether with one another—as together as a commonplace plate with a mouth:

what that’s really called—from the gut—

has this

mysterious infinity-loop of string dyed black.

Mysterious infinity-loop of string dyed black

has this

again—on the right hand—

mysterious infinity-loop of string dyed black.

The sun shining down like an eye on the people sees all this, sees

mysterious feminine essence–a few drops of that womanly mist–

has this

double-winged gateway.

~

Whaaaat?! I hope that’s your reaction, as it was mine when I built this. Don’t worry though—as we look at different characters and the way this chapter is organized, you’ll come away with some clearer sense of the parts and the whole. It’s still going to feel wild, though. That I can promise.

As we move through this book together, I look forward to your comments on what, I know, is a somewhat radical approach to this beloved classic. Please know that I have only respect for the received translations and for the traditions and lineages that came out of those texts. What follows here and in the rest of this project is my own fun investigation to help me directly experience this invaluable, mysterious document in a personal way. I hope it does the same for you.

Happy New Year and new decade!

Last tinkered with 3/10/20