ruò (若)

Within that valley mouth between two mountains,

a lightning god…

the husk of the initial protective bud casing—the sepal—but not really the true inner flower of

being mortal—going from a standing person to a pile of bones;

the sun—walking across the sundial a while, stopping a while—sees indeed

what it’s called when speaking from the gut—words, like slaves or criminals branded by a chisel emerging from a mouth,

the hard-to-see dark structure—like a figure-eight skein of string-dyed-black:

a mother’s lap—a cow with an arrow… a vagina.

“Hard-to-see dark structure—like a figure-eight skein of string-dyed-black,

a mother’s lap—a cow with an arrow… a vagina,

has this

double-winged gateway… “[from Chapter 1]

the sun—walking across the sundial a while, stopping a while—sees indeed

what it’s called when speaking from the gut—words, like slaves or criminals branded by a chisel emerging from a mouth:

Heaven (that sky level above the human head)-Earth (this soil vagina)…

root of the family tree—penis…

barely perceptible—like the fine, white silk threads making up that ever-present, timeless, whole head-cloth ‘ji’ our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads once they’ve received their adult, public courtesy-names.

Barely perceptible—like the fine, white silk threads making up that ever-present, timeless, whole head-cloth ‘ji’ our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads once they’ve received their adult, public courtesy-names…

someone compliantly combing their loose hair seems to be saying: ‘this is as if…’ (ruò, 若)

surviving—on the plane of a baby with health issues, maybe a large head, but still sprouting… (cún,存)

doing truly useful work like a water bucket—by means of carrying-capacity

has this…

the husk of the initial protective bud casing, but not really the true inner flower, of

exerting with force—working hard with the strength of an arm, a bladed tool, or a plough on the soil.

That’s all of Chapter 6 in its entirety. It’s a pivotal chapter because here we meet a new character, ruò, 若. Its bronze inscription character is a pictogram of a person combing their hair:

Its modern translations are to be obedient or compliant, to trim vegetables, to choose, you/yours, he/his, like, as if, and supposing. Dào translators usually interpret it as is like, seems, or as. Or they just ignore it altogether or use “is” in its place. In two key places in Chapter 37, the final chapter of the Dào part of the Dào Dé Jīng, they almost universally translate it as “if.” As is my custom, I incorporate the modern meanings, the pictogram, and the traditional translations into one consistent translation every where it occurs:

someone compliantly combing their loose hair seems to be saying: ‘this is as if…’

Since there are other, more specific, ways to say each of the traditional meanings (if, like), I think this character has some particular use for Lâozî.

~

It’s interesting that ruò so prominently features hair since that’s a recurring motif… beginning with The Way itself. In the character for Dào, the head very obviously has a head of big loose hair.

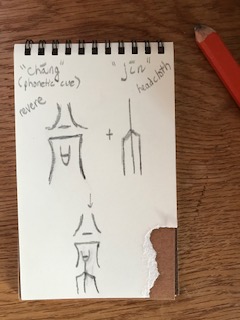

And in Chapter 1, right away we’re struck by how that seems to very obviously differ from the conventional hairstyle of a grown man with a top knot (fú, 夫) and especially from a grown man whose top knot’s covered by a traditional head cloth. This head cloth image occurs not only in that word for the timeless, never-changing traditional version of things (cháng, 常) but also in the characters showing God in Heaven or emperor (dì, 帝, as we saw in Chapter 4), barely perceptible (mián, 綿, as we see in this chapter), and sparse (xī, 希).

Hair style appears in many other characters including, not least of all, lâo, 老: an old man with long hair and a cane. This word is the first part of Lâo Zî’s honorific name.

~

It’s fascinating to me that this character ruò first appears in this particular place in our story. In Joseph Campbell’s classic Hero’s Journey story arc, this is the place where the hero would get outside help, usually from a supernatural, larger-than-life, or unexpected source.

In the last chapter, there was the doubtful sentiment of “pah, can you?!” The call to the daunting adventure of living according to The Way of the Loose-Haired Chieftain seemed rather undoable. But now we have someone compliantly combing their loose hair who seems to be saying: ‘this is as if’ surviving—on the plane of a baby with health issues, maybe a large head, but still sprouting.

Chapter 4 introduced the possibility of surviving. But here, our magic someone not only rather drolly says that’s what’s happening but elaborates what this means: the doing of truly useful work (like a water bucket) has this: non-exertion.

OHHHHH. Doing useful work like a water bucket without overflowing (while pouring water our from the center hollow drum!) was the calling for The Way at the beginning of Chapter 4.

So what does Chapter 6 tell us?

- Here’s the situation: The lightning god within that valley mouth between two mountains isn’t really turning into a pile of bones. Phew.

- The sun sees indeed what it’s truly called, that hard-to-see dark structure—like a figure-eight skein of string dyed black:a mother’s lap/vagina…

- and the “hard-to-see dark structure, a mother’s lap/vagina’s double-winged gateway” (remember that phrase dramatically ending Chapter 1?) is truly called… Heaven-Earth… root-of-the-family-tree or penis…

- barely perceptible. Mián, 綿, or “barely perceptible” is drawn by showing the fine, white silk threads making up that ever-present, timeless, whole head-cloth ‘ji’ that grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads once they’ve received their adult, public courtesy-names. The modern translation of this word is soft, downy, or sometimes cotton. Dào translators variously call it continuously, always present, like a veil, lingering like gossamer, or invisible.

As usual, the lack of punctuation and various potential syntaxes make those first five lines interpretable in many ways. Also as usual, I interpret it based on how the drawings and double-meanings make something occur to me. What with all the pregnancy and baby images, I’m starting to think that Heaven (tiān, that sky level above the human head)-Earth (dì, this soil vagina) refers to a spirit from above when it is down here, manifest, in the womb. In other words a fetus.

In the Western Zhou bronze inscription age just preceding Lâozî’s era, tiān was drawn as a person with a large head:

In the even older Shang oracle bone script, it was drawn with a line above a person’s head, supposedly indicating a higher level:

It is thought that the oldest meaning was sky. It’s also been used to mean heavens, celestial, heaven as a place for deities or departed souls, heaven as a deity, overhead, top, climate, a 24-hour day, daytime, season, nature, natural, innate.

So is my interpretation far-reaching? Maybe. But when I re-read everywhere this phrase occurs, it totally can fit this secondary-level interpretation at the same time that it fits into a meta- or symbolic story about “Heaven on Earth” or “Heaven and Earth.” In this use of it, I see someone literally trying to figure out what’s going on inside a laboring uterus and barely being able to discern the fetus. Maybe they can tell it’s a boy? Or maybe they know that after the fact. Or maybe the vagina’s product is called the family root, attributed to the work of a penis. Okay back to what we see for sure…

- Even though it’s barely perceptible, our magically helpful someone, compliantly combing their loose hair, seems to be saying: ‘this is as if’ it’s surviving —on the plane of a baby with health issues, maybe a large head, but still sprouting. Now you can see how, based on my imagination and the previous and following chapters, I like to think of our someone as a midwife helping with premature labor.

- And given this situation, she says that surviving means doing truly useful work like a water bucket, by means of carrying capacity, has this “not really exerting with force.” I see that as “the most useful work now is just to carry that baby. Don’t labor. Especially don’t push.”

There you go… I’ve fully bared my most wild, favorite theory. And you can understand my admiration for Lâozî, given that this story is buried within characters that ALSO can be translated as a cosmic, existential, life handbook. Here’s how Yi Wu translates this chapter:

The spirit of the valley never dies;

It is called the mysterious female.

The gate of the mysterious female is called the root of Heaven and Earth.

Continuously it seems to exist.

There is no labour in its use.

And here’s how Feng and English translated it:

The valley spirit never dies;

It is the woman, primal mother.

Her gateway is the root of heaven and Earth.

It is like a veil barely seen.

Use it; it will never fail.

Thomas Cleary translates it as:

The valley spirit not dying is called the mysterious female.

The opening of the mysterious female is called the root of heaven and earth.

Continuous, on the brink of existence, to put in into practice, don’t try to force it.

Is this non-forcing possible? Sometimes—whether because you’re in actual labor or you’ve found yourself in the habit of over-efforting in life and not relying on the “female” type of creativity—it doesn’t seem like it. Can our magical someone help in ways more tangible than just saying “don’t labor; don’t force it?”

We’ll find out next time. And now, until then, please use the contact form to send me your responses to my theory! I hope you’ll go back and re-read all the chapters we’ve looked at thus far and see how my ideas do or don’t make sense to you. Thanks for being here.