cháng

Here we have a compound character. What do you get when you combine cháng (尚), a character that meant to revere:

… with a character that depicts jīn (常), the square head cloth that males wore over their hair buns once they achieved full adult status?

Jīn’s own etymological evolution includes the word diào (吊) which uses a pictogram of a “small bird with a dangling tail” to describe the top knot. This bird and a couple others are sub-components in lots of words, as you’ll see in the future. But in the Western Zhou Bronze Inscription of Lâozî’s time, jīn looked like this:

Lâozî combined these two sub-components into a word, also pronounced cháng, that’s written in modern script like this:

常

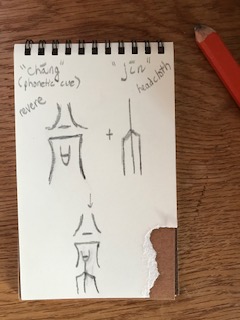

The two sub-characters shown above are in the Western Zhou Bronze Inscription script that I think were most like the script Lâozî would’ve used. But I can’t find an image from those times of the compound character, so… yes, I drew one. That’s what you see at the top of this post!

There are many such cases in the Dào where I can’t find a WZB version of a compound word that Lâozî used. (Of course, you can see how this plays into my theory that our brilliant Lâozî made up all these words a lá Shakespeare!) Hopefully I’ll either find these WZB hybrids somewhere on the internet or figure out how to draw them in a clean digital way at some point soon. Of course I must say that all such efforts are simply my best estimate as to how the two components were combined, based on looking at the modern character. Here’s a peek into my process:

It’s super fun. If you turn your hand to this and come up with something cool, please send it to me.

Meanwhile, what meaning do you imagine when we combine these two sub-characters? The first sub-component here, also called cháng, is considered to be the “phonetic” component that simply gives the compound character its sound. The real meaning—the “semantic” part—is considered to be the bottom component. Modern definitions include: normal, general, common, constant, and invariable. Indeed, the jīn head cloth was worn by every grown man, so it was a common, constant part of daily life and probably seemed like it had been forever.

Some Dào Dé Jīng translators, like Yi Wu, translate cháng to the simple word constant. But others, including Chen, Feng and English, John C.H. Wu, and Mitchell, think Lâozî meant something even more cosmic. They translate this character in Chapter 1 as eternal. But they also substitute other words in different places, depending on the context: always, constantly, never, abides, forever, and so on. Sometimes they don’t directly include this word but fold it implicitly into how something just “is” or “isn’t” something.

By now, you know I get frustrated when I’m reading a translation and can’t tell if I’m looking at the same word that was used in the paragraph before, the page before, etc. But of course, I understand why it’s done. It’s hard to make just one phrase make sense or even fit grammatically in every context.

And you also know what I’m going to do next: throw in ALL the things! To heck with brevity and certainty! The translation I use everywhere for this character is:

the ever-present square fabric which our grown men wrap around the ‘little bird’ top knots on their heads after receiving their public courtesy-names—or what we know as the timeless, whole-cloth ‘ji’ version of…

I like the square shape of the jīn… so pleasing. I love that this word includes fabric which to me relates to the revelation in yesterday’s post that the word xuàn shows us an infinity-loop of black thread! I wonder how else parts of this word will tie into other pictograms and concepts as we move on.

And when I step back and look at this phrase and how it’s normally translated as eternal or constant, I think it gives us a very particular sense that in ancient China, these traditions of becoming, being, and being recognized as an adult man were indeed very timeless, ubiquitous, and solid. And they were revered—which is why I think the “phonetic” component in this word actually contributes a lot to its meaning.

Of course, now when we look back at how cháng‘s used in Chapter 1, it’s even more interesting. But we’ll delve into that more and put it all together after we look at a couple more words in this chapter. Thanks for joining me here once more! I hope you’re settling into the uncertain, floaty feeling of this text and letting it wash over you without having to come to any conclusions. There’s some powerful alchemy at work, I just know it.

TINKERED WITH: 1/15/20, I replaced my paper-drawn composite of the Bronze Inscription components with a digital hand-drawn version.